Not only is Trevor Jackson a well-respected DJ and designer who’s lived in east London long before it was deemed hip, but his label Output, the imprint du jour, is to the 00s what Factory was to the 80s and Warp to the 90s. John Burgess bows before the connoisseur of cool…

Trevor Jackson has a complaint. He has made himself hoarse from talking. Several thousand words have been hurled from his gob in the last hour on everything from music to robots via silly haircuts. Famously passionate and occasionally combative, he grins, “I’ve not slagged anyone off today.” He sits and muses for a minute, thinking of a target at which to vent his spleen. But today he can’t think of anyone. He’s in positive spirits and has his labour of love label Output to talk about. After all, it’s releasing five albums this year.

There’s a mood of change running through the independent record labels which Output encapsulates. Like Factory, Warp and Mo’ Wax, Output is driven by the desire to release music primarily for creative rather than commercial reasons. The Output remit is also similar in that despite its diversity – musically and geographically – everything gels and boasts a strong visual identity. The likes of DFA, Kitty-Yo, Gomma, Flesh and Domino are ploughing a similar furrow; the passion for their art is tangible, staffed as they are by enthusiasts, DJs, writers, designers and promoters. Their prime motivation is getting their music heard because they feel it needs to be.

“You can’t do the same old boring shit anymore,” agrees Trevor. “The public aren’t idiots, they aren’t stupid. Human beings have a natural curiosity to find something different. If I can offer that difference then I’m doing my job.”

We are sitting in Trevor’s Hoxton flat, the phone line to which he has temporarily put on hold. Spike, his old black cat, is asleep on a white rug, looking, from a cursory glance, like a large ink stain. Fridge magnets are arranged with a message from LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy, which concludes ‘Big ups to fonk’. Betraying the 35-year-old’s passion for design, the walls are covered with film posters, Keith Haring prints and shelves stacked with art books. A wall full of vinyl has spilled across the floor, making it a potential hazard for anyone exiting the toilet. “My life is a stereotype,” Trevor admits with a wry smile. “I live in an east London loft apartment. I collect records, comic books and robots. But it’s genuine. I’ve done it since I was a kid.”

Though the phone is switched off, Trevor cannot settle. He’s up again, heading for the decks, eager to let Jockey Slut hear the remixes he’s just received for DK7’s ‘The Difference’. As the music booms forth, he looks like an excited kid who’s just pulled a new toy from gift wrapping. The music – vintage acid house – also dispels any notion that Output is a one-trick pony. Trevor is bothered that the punk-funk tag seems to have attached itself to the label and fears being seen as a passing fad. He becomes animated, pushing his hand through his big hair.

“The label’s been going seven years now, and it might have been easy to build up some contrived hype shit in the first few years, which I didn’t do.” he says. “I’ve just consistently put out good records, and I’d like to think people think there’s an integrity and passion about what I do and that it’s completely genuine. I don’t want to be seen as flavour of the month or the sound of now. I always wanted to kick against things, so with this punk-funk thing my immediate reaction is to change and do something completely different. The label is really diverse but the records have some coherence from the very first Fridge 7-inch. If you hear it now it’s live drums, analogue synth: a punky, electronic, live dance record. I’ve always been into rock records you can dance to, so maybe I’ve come full circle. But everything I do is genuine, that’s really important to me.”

Output was born of a series of catalytic events in 1996. Under the name Underdog, Trevor had been remixing acts as varied as House of Pain, Massive Attack, Run-D.M.C. and The Cure but had become disillusioned with the hip hop he was known for, feeling it had become too one-dimensional. He wanted The Brotherhood - the multiracial rap act he produced - to be looking deeper for their beats and to acts he grew up with: Public Image, ESG, Material and 23 Skidoo. But they had other ideas. “I kept coming up against a brick wall. My hip hop label Bite It had become a bit of a nightmare too. Then my close friend and manager died. It was a really bad time and I needed to do something fresh.”

Trevor found a kindred spirit in Luke Hannam (“the best bass player in the country”), and together they recorded an album for Acid Jazz as the Emperor’s New Clothes. Though the album never saw the light of day, the “psychedelic, weird jazz, post-rock-type stuff”, influenced by the beats of PiL’s ‘Metal Box’, put Trevor back on track creatively.

At Mo’ Wax he found a couple of open-minded hip hop headz in James Lavelle and Tim Goldsworthy, and he signed up as a DJ for their seminal night, Dusted. “I’d be able to play techno, hip hop and house, everything. I grew up on that eclecticism, hearing Afrika Bambaataa, Kraftwerk and The Clash. Mo’ Wax blew that hip hop purism apart. It was a genuinely strong movement, visually and musically.”

Initially, Output released Trevor’s own material: leftfield leftovers from The Brotherhood sessions. That all changed, however, when Trevor signed the then 16-year-old Kieran Hebden and his school band Fridge. “They were so prolific,” he recalls. “We did tons of singles. I don’t think the label would have existed without them.”

The success of Fridge meant that Output was then seen as being part of the burgeoning post-rock movement. “People have always wanted to put Output in a bracket, but I don’t see it like that at all. The name Output is generic and can relate to anything. If people listen to the ‘Channel 1’ compilation it’s completely different to ‘Channel 2’. ‘Channel 3’ will be different again. I’ve been consciously trying to get more bands, more songs.”

The recently released ‘Channel 2’ collates the best tracks from the last 12 months, all of which are beautifully skewed, well-crafted and varied. Grand National draw on agit-funk, Parisians Black Strobe and Colder look to New Order and Joy Division, respectively, Rekindle’s sugary pop sits next to the Luke Hannam-vocalled Tall Blonde and the tense, taboo sound of Canada’s Circle Square is balanced by the edgy but melodic 7 Hurtz. This is not “borrowed nostalgia from the unremembered 80s”, as James Murphy put it on ‘Losing My Edge’.

“The label is just about putting out music that I like. I know that may sound stupid but a lot of labels have other agendas. I put out stuff I like regardless of whether it’s cool or whether it will sell. All these people I’m associated with, we’re just like minds.”

This is reflected in Trevor’s relationship with New York’s The DFA - one that A&R types would gnaw their left knee off for – which led to the inclusion of The Rapture and LCD Soundsystem on the roster.

“We’re just mates,” he says. “I’ve known Tim (Goldsworthy) from the Dusted days. James Murphy and I got on like a house on fire, we’re very similar. Tim liked ‘Make It Happen’ and thought I’d be interested in The Rapture.”

Having one of the hottest bands on the label led to some surreal scenarios. Trevor bristles, exasperated, when recalling them. “When The Rapture came over to play some gigs I had A&R people phoning me up and asking if I could put them on the guest list. Why would I put you on the list so you can come to one of my gigs and try and sign one of my bands?” His hand is slapped across his face in disbelief, one eye peeping out for my reaction. Here comes the fighting talk. “Major labels are running scared. I can market my records better than anyone, I think I can design the sleeves better than anyone and A&R them better than anyone can. I don’t need anyone’s help. I’m going to stand my ground and do it as independently as I can.”

Trevor’s pop project Playgroup was first released on Source in late 2001. Though it was well received in the press, it failed to connect with the public at large, becoming little more than a cult opus. Following an agreement with Source, Trevor now owns the rights to the album which he’s putting out again this summer. In the interim ears have become accustomed to a more avant-garde pop sound, so second time around, in theory at least, the single ‘Make It Happen’ - which Trevor is most proud of - should find an audience.

“I’m in such a powerful position to own my own recordings, videos and artwork,” he says. “I feel like Prince or George Michael. I’d rather be putting something new out, but I can’t let it stay in limbo in a vault. People can’t buy it at the moment so if any copies are going to be out there they may as well be mine.”

Playgroup was Trevor’s attempt at pop, at a commercial record, so he’s at pains to point out that it’s separate from Output and is being released on its own imprint. It was also the last thing fans of The Underdog would expect from him. If The Underdog was appreciated by bearded bedroom technophiles, Playgroup was for house parties. “It was my way of being alternative after making noisy, abstract records,” he says. “In the UK only Blur and Pulp were making creative pop. When I grew up you had Soft Cell, The Human League and ABC rooted in club culture but making pop. That’s what ! wanted to do.”

The following day Trevor is at the Jockey Slut office – which is only a swift walk from his house – collaborating with our art director on the cover. He has lived in London’s EC2 for 17 years. “I know it’s seen as fashionable to live in east London, but I’d rather live here where people do something genuinely interesting than west London which is full of fucking idiots. Hoxton is seen as an insult. What’s that all about? If I went up to someone with a silly haircut they’ll probably be a web designer, fashion designer or someone doing something creative, and that’s great.”

Trevor’s primary trade is in graphic design. He made his name in the late-80s rave days with sleeves for the likes of Raze, S’Express, Jungle Brothers and Stereo MC’s. He has admitted that another, more selfish reason for starting Output was as an alternative outlet for his artwork. His inspirations are various, but when pushed he opts for Factory Records’ maverick Peter Saville, who taught him the importance of simplicity and classicism, and Barney Bubbles, who designed the Stiff sleeves for Elvis Costello and Ian Dury. Of the pop culture detritus in his flat, Jockey Slut unintentionally riles him by asking if most of the colourful, plastic toys are there because they are aesthetically pleasing. “I don’t own anything because it looks good. I collect icons of the 20th century. That’s the worst thing that’s happened in culture; that things have become facile and one-dimensional. If things don’t have a function then they’re meaningless.” When we point out a large grey robot and enquire as to its practical usage, Trevor says, matter-of-factly: “It makes tea.”

We meet again later that night in the Social pub, Islington. Since we last spoke he’s been interviewed by a German magazine about his five favourite records. They are, in no particular order, Thomas Dolby’s Flat Earth’, Nas’ ‘Illmatic’, Mark Stewart’s ‘The Veneer Of Democracy Starts To Fade’, Scritti Politti’s ‘Songs To Remember’ and Fingers Inc’s eponymous debut. Hip hop, house, post-punk and pop... as diverse as the Output roster.

“I’ve had a day like you would not believe,” he reveals over a soft drink. “I’ve been finishing the artwork for the 7 Hurtz album, finishing my XFM London X-press show, been interviewed by a magazine, and we’ve got the (Slut) cover done. I’m off to Paris tomorrow afternoon and then Brussels at the weekend to DJ with Soulwax and James Murphy. I’m sure I’ve forgotten something.”

He has. Other than the albums Output has lined up this year from Colder, 7 Hurtz, Tall Blonde and Circlesquare, plus The Rapture and LCD Soundsystem releases which he hopes to be involved with in some way, he’s forgotten to mention that he has another project of dirty demo-style outtakes called Pink Lunch and an untitled house project that he hopes to release. He’s also launching Input Records to release forgotten dance classics. Ze Recordings – that soundtrack to early 80s New York/London nightlife – is the first project, not least because Trevor grew up on Ze and now has the entire back catalogue. He twinkles as he runs through such luminaries as Kid Creole, Was (Not Was) and Material.

Talking in torrents with a couple of DJ friends about, unsurprisingly. music and DJs, Trevor admits that he never used to hang out with musicians. “I didn’t find people I could relate to, and now I have people I consider my friends who are also making music and we have the same agenda,” he says. “I’m thinking about DFA, Gomma, (Midnight) Mike and Flesh, Soulwax. There’s no name to that movement but we all feel the same way about something. We stand outside of what’s going on.”

Outsiders with ideals, friends moved by music, not money. No wonder the majors are running scared from this genuine global revolution.

Trevor Jackson and friends: make it happen.

Trevor Jackson's Six Of The Best...

The Brotherhood: ‘Alphabetical Response’ (Virgin)

“The first single. The photograph was taken by Donald Christie, who I’ve worked with for many years. I was into psychedelic rock and fucked-up krautrock stuff so the cover’s inspired by all that shit.”

Lewis Parker: ‘Rise’ (Bite It)

“It’s Lewis standing in a cornfield. This is a British hip hop thing, but Lewis is from Canterbury. He’s not from the urban streets of London, so I wanted to convey that. It’s him in the countryside, but it’s not like Arrested Development’s flowery shit.”

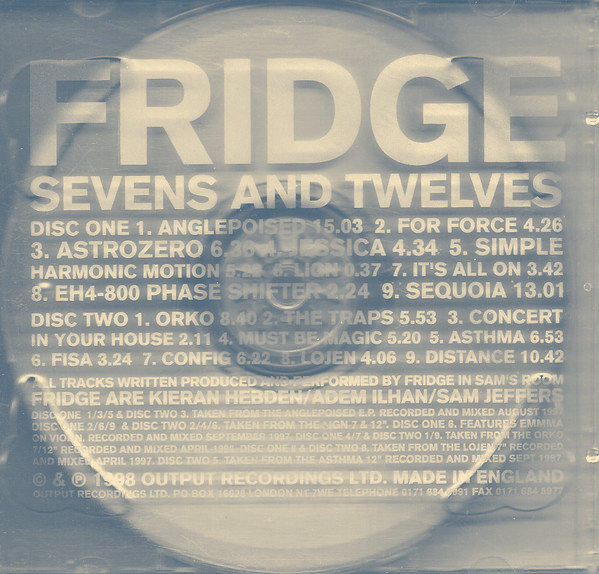

Fridge: ‘7/12’ (Output)

“It’s an experiment in screen printing, a weird, frosted type on the front. It’s been ripped off badly since then quite a lot. The packaging looks quite expensive but it’s cheaper than doing a normal CD cover.”

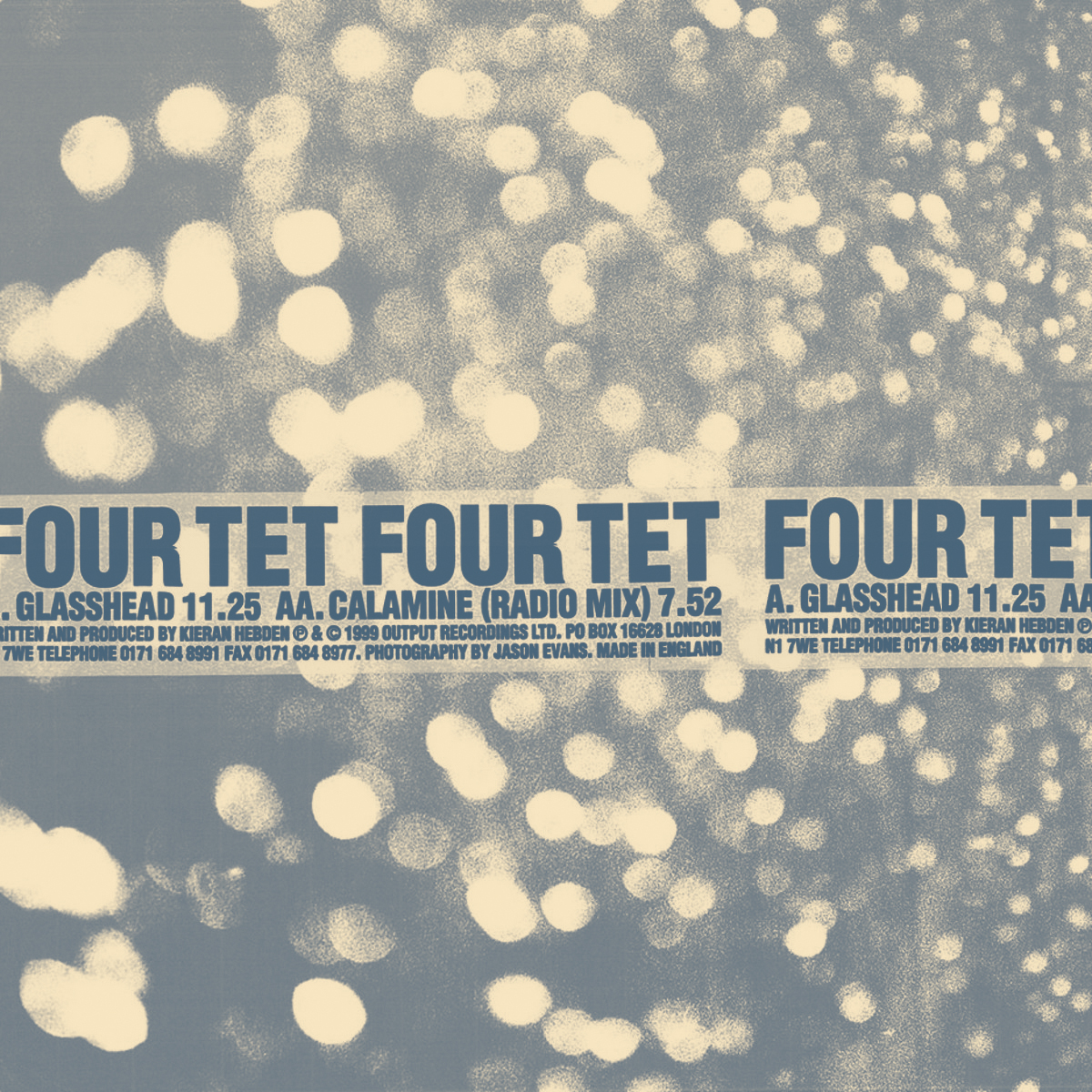

Four Tet: ‘Glass Head’ (Output)

“Even though we have to be careful with the money we’re spending on things we just had this great idea of using tape. We got hundreds of rolls of sticky tape made up with the tracklisting printed on and me and Kieran (Hebden) literally wrapped two thousand sleeves.”

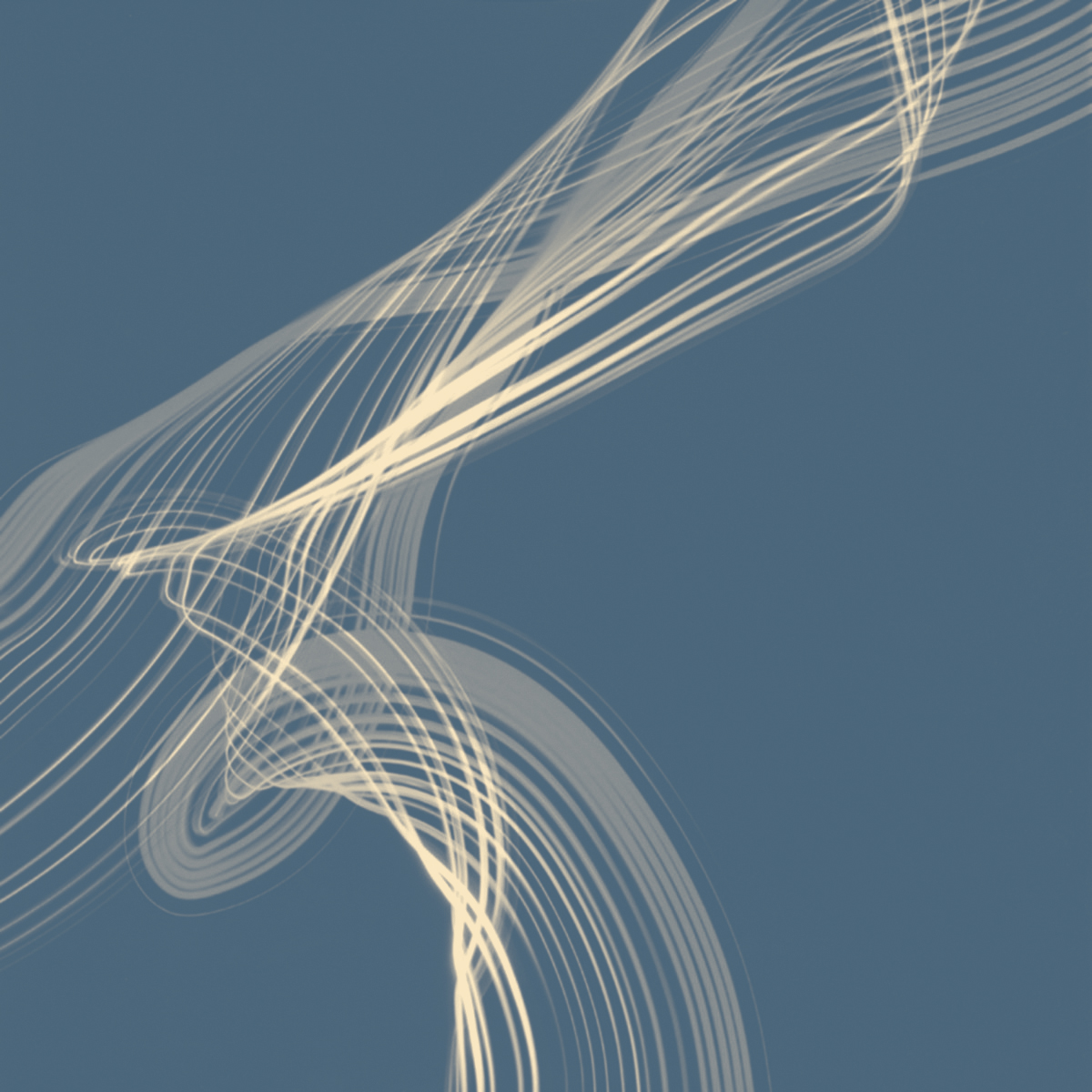

Playgroup: ‘Number One’ (Source promo)

“When we did the photo shoots for the album cover we experimented with lights, and I made this painting using lights. It’s like a piece of kinetic art.”

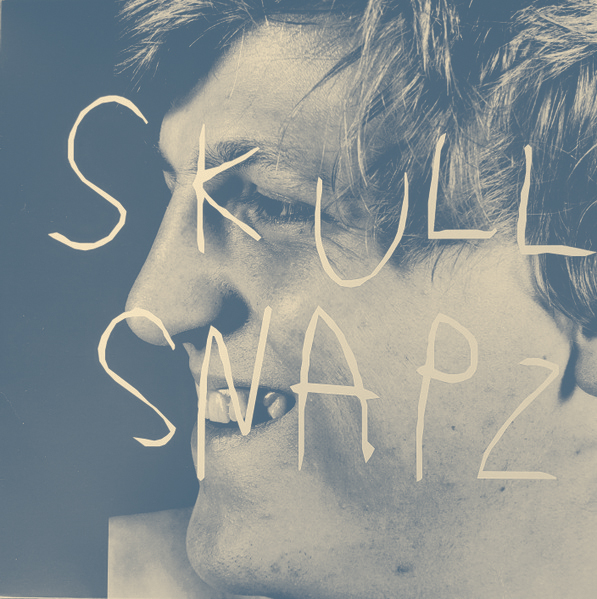

‘Skull’ EP (Bite It)

“It’s my music but I didn’t want people to know it was me at the time. Jason Evans photographed this guy Tim and everyone thinks he’s Skull. It’s raw, just a geezer’s face with the type scratched out on it. The music is avant-garde, fucked-up hip hop and the cover conveys that.”