Richard Russell has always been a fan. It’s this unadulterated passion for music that runs through everything he’s done: from his early love of hip hop through his rave hit ‘The Bouncer’ by way of XL Recordings, producing the final recordings of Gil Scott-Heron and Bobby Womack and writing one of the best music autobiographies of recent times. Now back for a third album with his sporadic Everything Is Recorded super collective (this time featuring Florence Welch, Bill Callahan and Kamasi Washington, among others), Russell tells Craig McLean why he remains an unabashed fan, stating: “If you’re a fan, you can’t get it wrong. You can only love it…”

The first record, amidst stacks – and stacks – of well-thumbed records, that you might see upon entering The Copper House is ‘Symphonie Pour Une Homme Seul’ by Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, a piece first performed by the pioneers of musique concrète in 1950.

Immediately above it, piled at the end of another shelf that stretches towards the kitchen area, is an LP by Barton McLean. It contains ‘Dimensions II for Piano & Tape’, ‘The Sorcerer Revisited’ and ‘Genesis’, the latter “realised” in 1973 “in the Electronic Music Centre at Indiana University at South Bend”, where McLean was the Director and teacher of composition, “on the Synthi 100 synthesiser, a massive and highly versatile instrument which combines the features of the traditional synthesiser with those of the computer” – at the time, the only such instrument in the United States. According to a fraying label stuck to the top of the sleeve, the LP was dug from the crates of one Ilhan Mimaroglu, of West 119th Street, New York. That’s presumably the Turkish-American musician and electronic music composer who died in the city in 2012, aged 86.

Above The Copper House’s kitchen area, the legend ‘Residence La Revolution’. In the middle of the floor, on a geometrically patterned rug, a jumble of electronic instruments. On the opposite wall, inscribed in firm chalk, the names and definitions of clouds: stratus (layered, flattened, spread out), cirrocumulus (mackerel sky, fish scales), cirrostratus (gossamer, foggy, vapour).

Leading down the stairs from the first floor, a message is marked on each of the treads, like a 12-inch remix of a haiku: “I tried to send you. A text message. Around 4:00am. Sunday but I didn’t. Reach you. I only wanted. To tell you that I had a great. Time with the project. Take care of your family. Maintain your calm. And stay safe. Everything else. Will be all right. Bless you.” This descending benediction is overlooked by a sole image hung on the stairwell, a black and white photograph of Gil Scott-Heron, suggesting that he’s the author – although the master of the house would prefer to keep that detail private.

And up those stairs? A studio where the owner of The Copper House – producer of Scott-Heron’s final album, 2010’s career-reviving ‘I’m New Here’ – does what he does in as rooted-but-booted a way as possible. The small space is busy with gear but calm; inspo in every direction (Laurie Anderson’s ‘Big Science’ on the turntable, tracklistings on the wall, a Hermann Mayr upright piano with its guts exposed and mic’d); comfy with its own funk shui. It’s anchored by the studio’s foundational equipment, an avowedly easy-to-use, 1972, 16-track API mixing desk sourced from Detroit. “A beautiful thing to look at. It’s simple. It’s small. And it has a sound, and an analogue warmth. We look after it, service it every year, replace parts. We’re recording everything through this.”

From recording everything to Everything Is Recorded. As Richard Russell – the DJ-turned-rave-act-turned-A&R-scout-turned-label-boss-turned-DISCOVERED-ADELE-turned-producer-turned-artist – puts it: “I’m not really a musician and I like working with people who are more accomplished musicians than I am.

“But I also like working with people who are not musicians at all,” he adds. That’s a (likely) reference to Samantha Morton, the Oscar-nominated actor with whom, last year, he made an album, ‘Daffodils and Dirt’, under the joint name SAM MORTON. She also appears as a vocalist on ‘Temporary’, the expansive but intimate third studio album from Russell’s multi-artist collective, Everything Is Recorded. It comprises 14 tracks, with seven more waiting in the wings for an additional release, its roster of some dozen-and-a-half contributors marshalled by Russell from the The Copper House, sun-like centre of his many musical worlds.

“It’s interesting, to see what people do, how they put their hands on [musical equipment],” continues the 53-year-old who, as an indie label executive (and ultimately co-owner), helped turn XL Recordings from a rave imprint into the powerhouse home of The Prodigy, Dizzee Rascal, The xx, The White Stripes, Radiohead, The Avalanches, Basement Jaxx, Adele and many more. “So that’s been a big factor in having this space. This is as simple as it could possibly be. And things can be made quickly and instinctively here. You can just put your hands on stuff and use it. There’s nothing in here which is like a museum piece.”

The freewheeling Everything Is Recorded project might be Russell’s own ‘Symphony for a Man Alone’. It’s a long (a very long way) from his first artist incarnation, as half of rave duo Kicks Like A Mule (the one-hit wonders behind 1992 Top 10 single ‘The Bouncer’). But there is, at the same time, as we shall see, a red-thread of consistent creativity throughout.

He initiated EIR in his mid-40s, after his recovery from a life-threatening illness. But to populate the rich in atmosphere, folktronica soundscapes of this third album he has, as ever, roamed far and near. ‘Temporary’ features the versatile and varied talents of Florence Welch, Sampha, Berywn, Jah Wobble, Noah Cyrus, Bill Callahan, Kamasi Washington and the jazz-disruptor’s flautist dad Ricky, a sample of the late Nick Drake’s mum Molly, and English folk queen Maddy Prior. The latter is the former Steeleye Span singer, to whom Russell was hipped by Vampire Weekend’s Ezra Koenig and Jack Peñate, both of whom he signed to XL and both of whom helped him record the 77-year-old near her home in Cumbria.

Aren’t friends eclectic?

Here in Notting Hill, west London, it’s a cumulonimbus (hail, deep, dark, bases) kinda day. But inside The Copper House, the magician’s lair of Richard Russell, all is imagination and light and the smell of burning sage. Or is it cedar? We’re possibly not spiritual enough to know and definitely not as spiritual as Russell. This is a man for whom the phrase “in tune” contains multitudes. As he said in a statement teeing up the release of ‘Temporary’: “My experience of the people that I work with is that they are all deeply, deeply spiritual. If you’re channelling music, that’s the game you’re in.”

In his thought-provoking, bpm-powered 2020 memoir ‘Liberation Through Hearing’, Russell recounted how, around the age of 40, newly contemplating his mortality, he’d begun “devouring” books with titles such as ‘The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying’, ‘Letters from a Stoic’ and ‘Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind’. “Eckhart Tolle’s ‘The Power of Now’ and ‘A New Earth’ took on biblical significance,” he wrote. Then in 2013, aged 42, things got really biblical: Russell was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome, a brutally painful neurological condition which left him temporarily paralysed.

He was struck down just as work began to convert The Copper House. It was an architect-designed dwelling that, unavoidably rich on the millions that Adele and co. had brought XL Recordings, Russell bought from the then-occupant (“she told me what she wanted for it, and I said, ‘done’”). He was intent on turning it into what he needed most: a home studio that was neither in his home nor in the nearby offices of XL. He’d been on a trajectory out of the indie label C-suite since pivoting, four years earlier, into production with the Scott-Heron project.

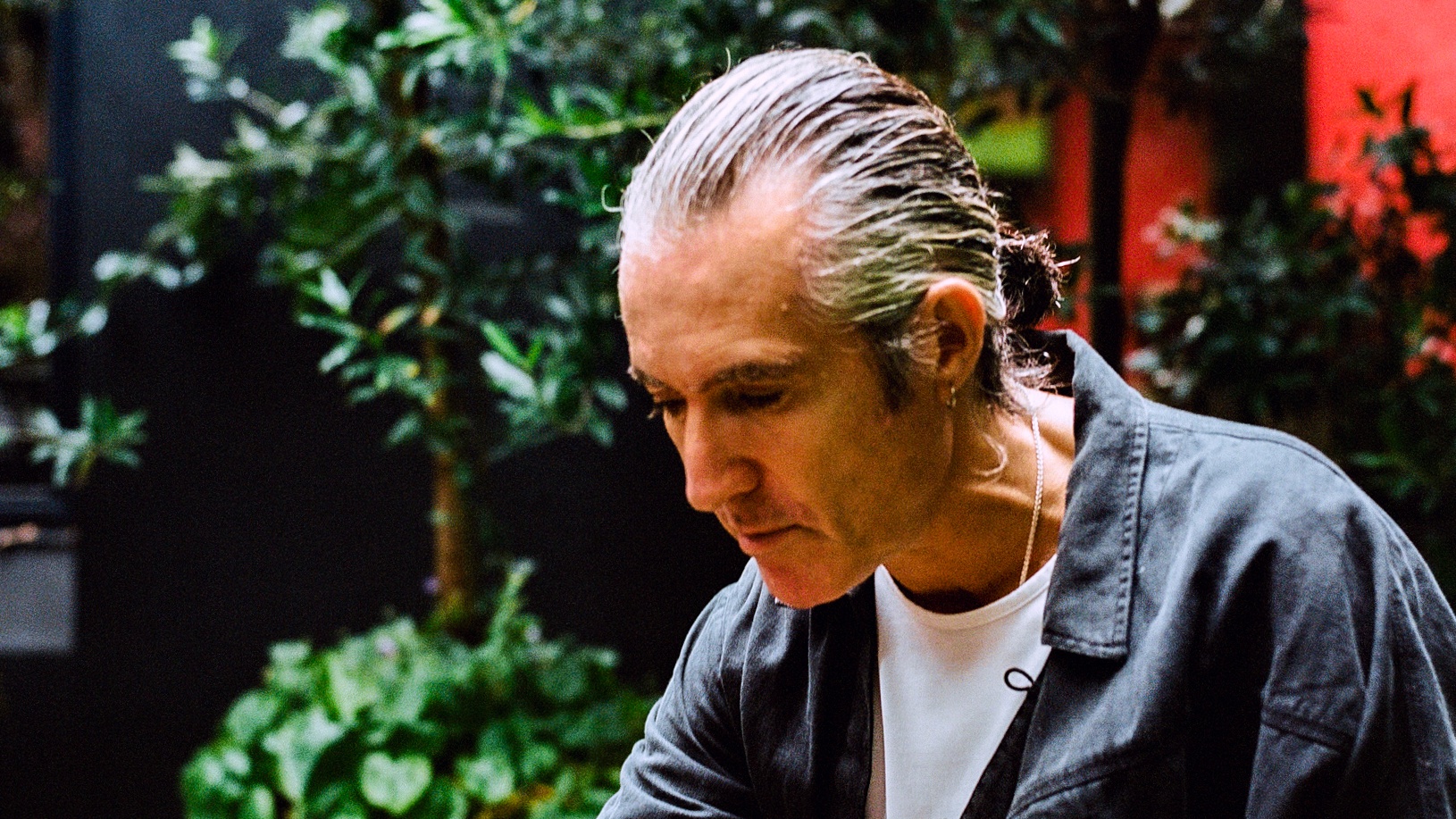

“That was an absolute turning point,” Russell – cross-legged and pony-tailed, a rave monk in tinted glasses and flowing layers, faithful terrier mix Bobo by his side – confides over a cup of hot water. “It was Gil saying to me: ‘Is this what you do now? I wasn’t sure this is what you did. This seems to be what you do, because we’re doing it. But is this what you do?’ I felt like he was putting me on the line. And in answering that, I was committing to something.”

It was a turning point, too, for Jamie xx. Russell, whose team had signed The xx when the south London band were barely out of school, asked the quietest member of a quiet band to remix ‘I’m New Here’.

“That was super important,” Jamie xx tells us of a project, retitled ‘We’re New Here’, that was released in 2011, when he was 22. “Obviously, I was so naive. But that’s why it was important. I was just so excited to make something, to be asked to do something, that I barely thought about it. I made it quite quick, in my house in Brixton. There are no stems of it that exist because I just bounced it out of my computer and that was it, I sent it to XL. It was a really nice, naive way to start the solo career.”

Russell, then, was a key figure in the creative maturation of a musician turned producer/DJ who’s now as big as his day job band (if not bigger). And for Jamie xx, his former label boss remains a quasi-talismanic figure.

“Richard’s very good at getting very deep, very quickly!” he says approvingly. That thoughtfulness and rigorousness, he continues, “has trickled down as well. Especially when he used to be at the XL office a lot more, when [The xx] started out. You could see it permeating all the different people that worked there and the vibe. And then it transferred over to Young,” he says of the imprint (formerly Young Turks) to which The xx are signed. “He was very inspiring. And that whole energy is very inspiring.”

Today in The Copper House, the rain drumming off the cuprous exterior, it’s clear what Jamie’s on about. “There was a parallel between the experiences Jamie and I had making those records,” Russell is saying. “Jamie was making an album on his own for the first time. I was producing an album for the first time. He was in his early-20s. I was getting on for 40. Gil was about 60.”

Russell – who alternates between a rapid-fire tumble of ideas and a more thoughtful, rhythmic, repetitive, almost hypnotic style of speaking – pauses. “That’s meaningful,” he goes on. “Because there I am, right in the middle of these two different generations. I was able to be a connecting force between them. And I’ve found myself in that position a few times. That’s a special position to be in. You can really do stuff with that. I get that that’s unusual. You can’t really contrive it. You can just find yourself there for reasons that are a bit beyond me, really. But I do find myself there.”

Finding himself there, in the thick of it, by following his nose, and his ears, has always been one of Russell’s innate skills.

Raised in northwest London, Russell was a hip hop-loving teenager who was there at the birth of rave. An avid DJ and club-goer from his mid-teens, in 1990, on his 19th birthday, he flew to New York on a cheap Air India ticket. He promptly landed a dream gig, working at Vinylmania. As he wrote in ‘Liberation Through Hearing’, the West Village store was a DJ mecca that was “an up-to-the-minute treasure trove of nothing but vinyl, glorious, exciting black wax, mainly dance music, some hip hop and R’n’B”.

Back in the UK the following year, he joined the recently launched XL Recordings as a scout – although when Kicks Like A Mule released ‘The Bouncer’ the year after that, it was on another dance-focused indie, Tribal Bass. The scene was popping off, with XL in the thick of it: also in 1992, they released another breakbeat hardcore belter, SL2’s ‘On a Ragga Tip’, followed by ‘Experience’, The Prodigy’s debut album.

“Which was not completely explainable,” Russell reflects now, marvelling at the label’s early, back-to-back success. “It was three people in a basement with a photocopy machine. There was magic to it, for sure. And there was also magic in the scene at that time,” he adds, giving due credit to other crucial labels of the time: Shut Up and Dance, Moving Shadow, Suburban Base, Formation, Reinforced. “These labels were incredible. XL was not categorically any better than any of those other labels. If you look at the [the different labels’] tunes, it was all really one thing in that moment.”

Steeped from his teens in the values and vibes of labels and studios and club culture, and the magic to be made therein (and you won’t find a more vibey place than The Copper House), Russell is a peerless, passionate connector and conductor. Setting a template for future kaleidoscopic roll calls of vocalists, the first Everything Is Recorded album, 2018’s self-titled Mercury nominee, featured Obongjayar, Giggs, Owen Pallet, Peter Gabriel and Green Gartside.

Equally, perhaps emboldened by a two-decade career in the music industry in which he helped develop the careers of talents as visionary and strong-willed as Adele, Liam Howlett, Jack White, MIA, Tyler, The Creator and late-period Thom Yorke, he is, too, clearly a collaborator who doesn’t shy from a challenge. After all, the second project he produced turned out to be the final album by another troubled icon of Black American music, ‘The Bravest Man in the World’ (2012) by Bobby Womack. The third was ‘Everyday Robots’ (2014), the debut solo album by Damon Albarn. On both those records, Albarn – no pushover in the studio – was his co-producer.

I last interviewed Russell in 2020, ahead of the release of the second EIR album, ‘Friday Forever’, a “concept record exploring the universality of a Friday night out, starting at 9.46 on a Friday evening and ending at 11.59 the morning after”, which featured typically diverse Russell heroes Ghostface Killah and Penny Rimbaud from punk band Crass. I asked him then for an Albarn story.

“Where do you begin?” he answered with a laugh. “OK, we’re in a Parisian boîte. This is when we’re playing with Bobby Womack on French TV. I’m talking to Damon in this club and he suddenly dematerialises… I look round and he’s sprinting to the dancefloor. They were playing The The, ‘This is the Day’, quite an unusual song to hear in a club. But this is one of Damon’s favourite songs of all time. So, he starts dancing, on an empty dancefloor… completely free, untethered. The female DJ sees this. I watch her do a double-take – ‘that’s Damon Albarn!’ And she abandons her post – which is not on for a DJ – and joins him on the dancefloor and starts having the time of her life.”

I think through the artists Russell has signed, developed, shaped, alchemised over the years, whether on their own records or his. That could be Damon Albarn. It could be Liam Howlett. “The thing with Liam Howlett was that he was a great producer,” he said five years ago. “So much of it with these rave records was about the drums. We were all frustrated hip hop producers; we wanted to make those records that had those incredibly exciting drums that were usually sampled from funk records. What Marley Marl made, what The Bomb Squad made – we wanted to do that. But Liam’s drums were the best of everyone on the rave scene at the time. Because they were simultaneously really stupid and really clever. He was also an actual musician… and authentically punk in his outlook. He had it all, that rare package, every possible strength. So, it was very irritating for him that ‘Charly’ was seen as a novelty tune. The same way it was for us with ‘The Bouncer’. But Liam didn’t let that knock him off course. And he’s made a lifetime career out of the noises he wants to make. That’s inspiring.”

That could be Adele (the “discovery” of whom he’s quick to credit to various members of his team). “She knew exactly what she was doing, and more,” he says now. “She liked the idea and the environment of XL. But she was like: ‘Yeah, it’s a bit trendy, though, and I’m not doing that. Here’s some people I want to work with…’ And they were these pop writers and producers who I’d never worked with. I was like: ‘Interesting, not what I thought she was gonna do…’ I thought she was gonna be folky, because that’s what it was on stage. And what I was able to add to that, correctly, was nothing. Just getting out of the way and not having some unnecessary opinions… It’s about listening.”

So, from Liam to Adele to Damon to, on ‘Temporary’, Florence – one wonders if a throughline in all this is Russell’s first “proper” job in the music industry. That is: once an A&R, always an A&R. He thinks for a minute. “I mean… once a fan, always a fan,” he counters. “That’s the foundational aspect of it. The A&R thing’s a bit dangerous. One of the reasons that A&R has a bit of a bad name is that it’s a difficult job. Especially in most of the places where you could actually earn a living doing it.”

You mean major labels?”

“Yeah. There’s a lot of pressure there. People are not able to just be a fan. They’ve got to think: ‘Where’s the hit?’ That obviously creates a lot of issues and a lot of friction. But if you’re a fan, you can’t get it wrong. You can only love it. What fan’s ever been wrong about that? ‘Why do you love it?’ ‘I don’t know.’ ‘What’s the connection between these five different artists you like?’ The connection’s you, the fan.”

For Russell, the dancefloor has always been a place of fandom and of transcendence. ‘Liberation Through Hearing’ is thick with playlists and flyers from nights he ran or spun at as “Rich”, one of the members of Housequake Productions, “our attempt, often inept, to emulate the London sound systems of that moment”, as he put it in his memoir. He can still namecheck cornerstone tracks from his teenage hip hop sets: 1988’s ‘Ain’t Nothin’ To It’ by K 9 Posse and, from the same year, Supreme DJ Nyborn’s ‘Versatility’, although preferably the ‘Versatile Extension’ remix.

“These songs both had really long intros. That was part of it – I was a technical DJ, and I used to like playing around with the drums. So those songs were key.”

The militant values of his early years in the rave and club trenches – fast-moving, no frills, DIY – echo through our conversation when he talks about a track on ‘Temporary’. ‘My and Me’ is the first full track after the sound collage/acoustic guitar/spoken word overture of the album opener, ‘October’. ‘My and Me’ features a flute solo by Ricky Washington, who tours with his son Kamasi.

“That’s one of my favourite moments on this record. That is a spectacular bit of playing – and the type of playing that I’ve never really allowed myself to record before.”

In what way?

“Because it’s not very hip hop and it’s not very punk and it’s not very minimal. And I’ve always been nervy about being in a more musical world like that. Like that could be indulgent or something like that. Initially I was trying to make a record without any drums on it, because I thought that was gonna push me. And I always rely on [being pushed]. So, I thought, let’s take that away. That’s a crutch. And in retrospect, that meant I had to focus more on melody, more than I’ve ever done before.”

But suggest that also means he’s had to part-exorcise his lifelong passion for breaks, beats and bleeps, to make a sprawling, almost ambient in places, folk-leaning record and Russell pushes back.

“I don’t feel that. I feel like it’s just done in a subtle way, befitting the era I find myself in. That’s all!”

So, you’re still a raver at heart?

“Yeah, I was making a rave tune this morning. I can also see how, maybe from the outside, that this music and the making of a rave tune, they’re different. But it doesn’t feel that different to me.”

This article first appeared in issue seven of Disco Pogo.

.svg)

.jpg)

-min.jpg)