For techno and house legend Kevin Saunderson music has always been more than a solitary concern. Saunderson has long embraced the notions of community, friendship and celebrating the city where he grew up and which made his name. Today, that idea of musical camaraderie extends to his own family, as he returns to his e-Dancer guise with his son Dantiez in tow. In a wide-ranging interview, Saunderson looks back on his past (Detroit, formative trips to Paradise Garage, Inner City, that Reese bassline…) and to the future, as he tells Ben Murphy, “the scene is always evolving…”

“You can’t take that legacy away. I think it’s more respected now,” says Kevin Saunderson, reflecting on the dance music heritage of his home city Detroit. “There’s a new exhibit that just went up about Detroit techno at Michigan State University. You have the Belleville Three at the African American Museum in Washington DC. So, it’s spreading.”

That musical heritage is something Kevin Saunderson had a key role in shaping. As part of the Belleville Three, along with Juan Atkins and Derrick May, he’s considered one of the original innovators of techno — the Black American dance genre that began in Detroit, alchemising disco, funk and advanced electronics into a thrilling new form. Saunderson’s group Inner City, with vocalist and songwriter Paris Grey, had huge chart hits in the UK, getting to number four with their debut single ‘Big Fun’ and number eight with the follow-up ‘Good Life’ in 1988, and scoring two Billboard Dance Chart number ones in the US, in the process introducing a sleek, chrome-dipped electronic groove to the mainstream. Throughout all his pop success, Saunderson maintained a host of underground pseudonyms, frequently inspiring dance music trends and even new genres with his releases as Reese, Tronikhouse and e-Dancer.

It’s to the latter that Saunderson is returning in 2025, with a new album, over 25 years since his classic ‘Heavenly’ record. On ‘e-Dancer’, he’s joined by his son Dantiez, a highly accomplished DJ and producer in his own right, for a fresh recalibration of the classic Saunderson techno sound. It’s an exceptional record, filled to the brim with 4/4 behemoths built to turn warehouses, clubs and festivals into scenes of sweat-drenched pandemonium. The shimmering synth riff of first tune ‘Melodica’ rides over brooding deep bass and a kinetic rhythm track; ‘Dancer’ is a spine-tingling blend of vocal samples, warping sub and percussive heft; ‘Bring the Funk’ mixes deeply swung drums with sinuous keys; and ‘Feel the Rhythm’ is simultaneously super spaced-out and locked in a groove.

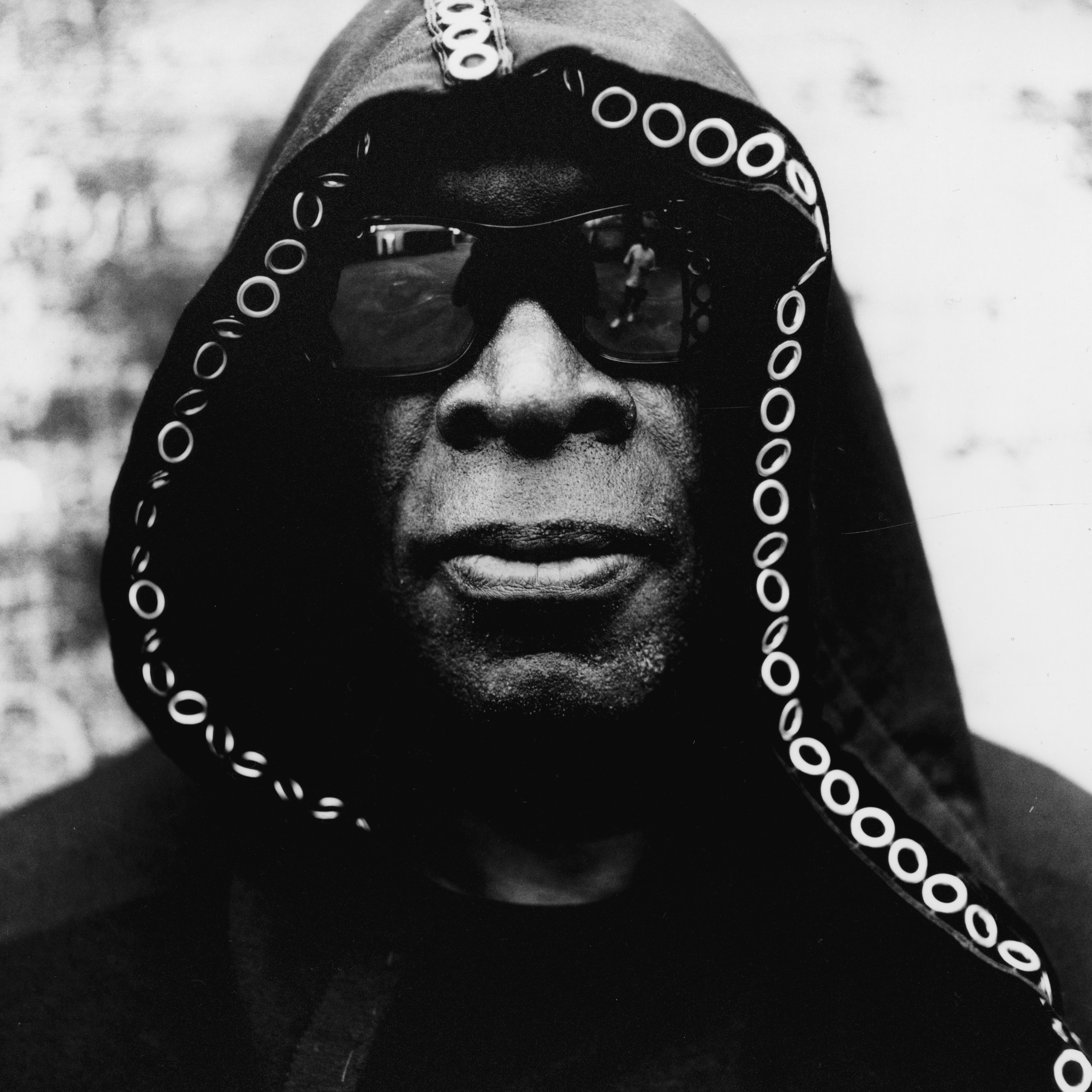

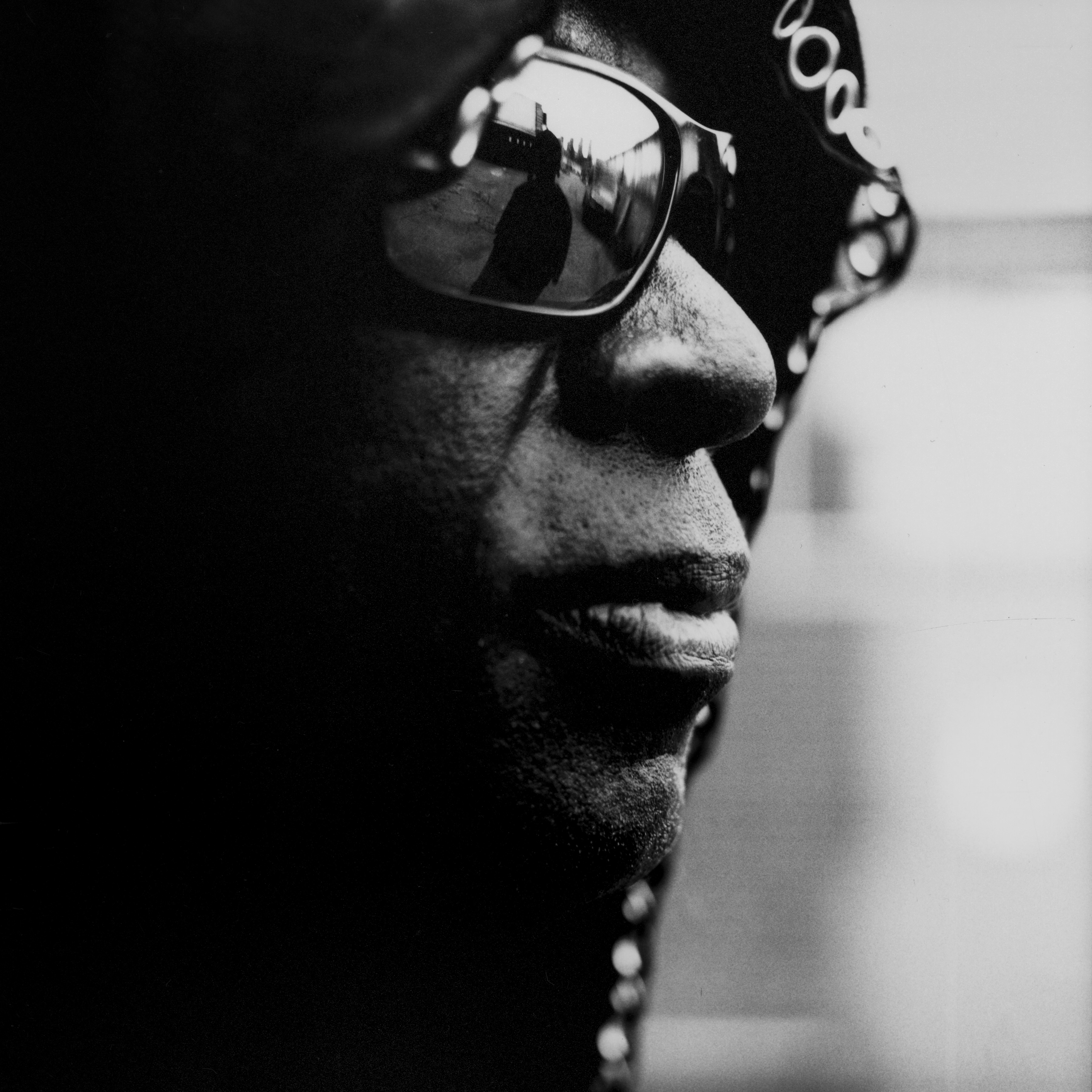

Speaking to the Saundersons, it’s evident they’re proud of the record. As we talk, Kevin is wearing a Detroit Versus Everybody hoody, while Dantiez sports long dreadlocks. When we ask how Dantiez got involved with the e-Dancer project, you can hear the father and son’s evident rapport.

“I walked in the studio and said: ‘Hey! This track sounds like mine,’” Kevin says, “and I played a record for him. He was like: ‘Oh, I see what you mean.’ I said: ‘I guess you just got my genes, don’t you?’”

“I did hear a lot of those records in the car and in the studio growing up, so obviously it’s imprinted,” Dantiez says.

“So, that started it again,” adds Kevin. “I said: ‘You just come on board as e-Dancer, it’s time for an album.’ It’s like: ‘Ok, let’s go back to doing something raw and real.’”

Though you can hear Kevin Saunderson’s distinctive sonic identity throughout ‘e-Dancer’, with those epic synth moods and dynamic rhythms present and correct, there’s something new, too: a more percussive feel and aspects that you just wouldn’t have got in his previous works. Dantiez reckons that his approach to production gives the new e-Dancer music a fresh character.

“I bring something different sonically,” Dantiez explains. “I use a couple of vocal samples that wouldn’t have been used in original e-Dancer tracks, a little bit of my flavour. A lot of these synths are newer that I’m using, so it’s newer sounds, different soundscapes.”

It’s remarkable that Kevin Saunderson is still making vital music, nearly 40 years since his first release. He was born in 1964, and spent his early years in Flatbush in Brooklyn, New York. When he was around 10 years old, his mother decided to move them to Inkster, Michigan, where she grew up. A year later, they settled in nearby Belleville, a middle class suburb of Detroit. For Kevin, it was a huge change from the big city, in more ways than one.

“It was quiet, country… stuff that I wasn’t used to,” he recalls. “It probably calmed me down, as I was pretty hyper as a young kid, trying to find my path and do something that stimulated me. But it was also a very racist town. Racist remarks, people throwing trash in our yard. I got involved in sports, and I think it helped me maintain.”

He played American football, basketball and ran track, but soon music would come into the picture too. He befriended Derrick May at high school, who introduced him to the enigmatic radio host The Electrifying Mojo. The DJ would broadcast on Detroit’s WJLB station, and his shows broadened Kevin’s mind on the multifarious nature of good music, with Mojo’s eclectic blend of funk, soul, rock, electronics and post-punk.

“I had stuff that I liked at that time, but Mojo was different, ’cause he helped me fall in love with artists like Prince, Parliament/Funkadelic, New Order, Tangerine Dream, B-52s. A great collage of music including, eventually, Juan Atkins.”

Kevin got to know Juan through his brother Aaron Atkins. By the time Kevin was at college in 1982, Juan Atkins’ outfit Cybotron (with Richard Davis) had released the futurist electronic dance singles ‘Alleys of Your Mind’ and ‘Cosmic Cars’, some of the earliest rumblings of what would later become techno. Derrick May had moved to Chicago, and then six months later, Kevin started hearing a different sound on Detroit radio.

“I heard a DJ on the radio playing all this house music – ‘Time to jack, jack, jack, jack your body’. I was like, ‘wow!’ It was cool, but they would never say who the DJ was. He would just be playing these mixes late at night. I find out that Derrick had moved back to Detroit and somehow got himself hooked up on the radio doing these mix shows with house music and whatever Detroit music there was, which was only Juan at that time.”

Kevin got further inspired by two friends on campus at Eastern University, Art Payne and Keith Martin, who had a great collection between them of early house and European dance records. A few years later, he decided to make a record of his own. Drawing from all his influences, ‘Triangle of Love’, made under the name Kreem, mixed a throbbing arpeggio bassline with raw drum machines and the kind of big female vocal you might have heard in New York freestyle or boogie records of the era. Released on Juan Atkins’ burgeoning Metroplex label, with some of his additional studio input, it set Kevin on the path.

“That early record was a collage of influences, but also experimentation, trying to figure out how to make a record and then make it work with vocals, because I was the only one trying to make a proper vocal record at the time,” he says.

“Juan actually replayed the bassline, which I know is kind of close to New Order too,” he laughs. “He came in and helped me finish the song.”

Having spent his early years in New York, and going back to NYC to visit his siblings, Kevin also went to the Paradise Garage. His love of disco and what came after would inform his next, and most well-known project, Inner City, with singer and songwriter Paris Grey. Several of his instrumental releases, like ‘Bounce Your Body to the Box’ and the wicked, sample-driven ‘The Sound’ were successful, but Kevin wanted to make something different, with vocals and actual songs. Having forged some strong links with DJs in Chicago, one day, he was told about a promising singer who could be just the collaborator he needed.

“I met this guy named Terry ‘Housemaster’ Baldwin, we became cool,” he remembers. “He worked with Paris before I worked with her. He came to Detroit and just hung out. I was playing him stuff that I was working on, instrumentals, and I played the music to ‘Big Fun’. He was like: ‘Wow, my singer would tear this up man, you should give her a shot, let her sing and write to it.’”

Saunderson had a vivid vision of what he wanted Inner City to be. He sent Paris Grey some music and asked her to try writing vocals for it. There was instant chemistry and Kevin knew they were onto something special. “I was like: ‘Ok, I don’t want no love songs, I don’t want anything negative, I want to stay positive, to keep it uplifting.’ She came with the perfect first track and second track. She wrote to it, I listened to it on the phone and I brought her back to Detroit, ’cause I was thrilled to get her in the studio to sing it.”

‘Big Fun’ and ‘Good Life’ were the sensational result, two tracks that sounded futuristic but also rooted in the heritage of disco, with their trippy synth stabs contrasting with Paris’ sublime voice and celebratory lyrics. Closer to the music of Chicago than the nocturnal electronics of Juan Atkins’ Model 500 material, they were essentially house tracks, but the inclusion of ‘Big Fun’ on ‘Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit’ – a landmark compilation in the UK put together by Neil Rushton and May – gave them a different trajectory.

“I went with the flow,” Kevin says. “I was just making a record that I thought would work as a dance record. I wasn’t trying to be a futurist. It got on that ‘Techno!’ compilation and of course then we had good press from The Face magazine and NME. But I would say it’s more house than techno.”

Saunderson knew he was on to a good thing but couldn’t have anticipated how successful the tunes would be. Coming to the UK in the summer of 1988, when acid house fever was at its height, he got a glimpse of the power of ‘Big Fun’.

“It seemed like somebody had just turned on the switch! I went to Heaven, Paul Oakenfold was playing at his night Spectrum. I was in the club just hanging out. He played ‘Big Fun’ and I’ve never seen so many people rush the floor. That’s when I knew I had something special. You could just feel it through the energy of the people.”

Concurrently, he was working on underground material. His track as Reese, ’Just Want Another Chance’, was a haunting mix of eerie synths, jacking drums, spoken word vocals and a rumbling, subterranean bass that seemed dredged up from the depths of the earth. That bass sound would end up sampled endlessly in the jungle/drum’n’bass scene in the UK and remains a staple of almost every dance genre today.

“Years later, I was hanging out with Fabio & Grooverider, and they were playing drum’n’bass. Every record had the Reese sound – they sampled my bass. I was amazed. You might hear one person sample your record, but it was like every record. I was like: ‘Damn, I wish I could have copyrighted that!’” he laughs uproariously. “But that’s technology for you, it allows you to be experimental in different ways. It wasn’t sampled in a way where it was disrespectful, the sample was a sound with replayed notes to create a different feel.”

And inspiration soon proved to be a two-way street. Saunderson was spending a lot of time in the UK in the early-90s and absorbed some hardcore and jungle influences into his own music. As Tronikhouse, he fused Detroit techno with breakbeats and rough ravey synths. His tracks ‘Uptempo’ and ‘Straight Out of Hell’ became favourites on the rave scene as a result.

“It was an inspiration for sure,” he says. “I thought breaks were cool, so I came up with my own feeling to put over the breaks, you know? Hearing Fabio and then going to some big raves like Raindance and seeing The Prodigy perform… whatever was going on at the time in the scene, I was experiencing. I didn’t want to sound like the UK, but I wanted to take some of what I liked and put my own vibe over it.”

Saunderson continued to have hits with Inner City, notably 1992’s all-time house classic ‘Pennies From Heaven’, but in the late-90s, he decided he wanted to focus on his instrumental, more overtly electronic sound. Reviving an old moniker, e-Dancer, he released 1997 album ‘Heavenly’, a masterpiece of metallic machine soul. From the mystic atmospherics and bubbling bass of ‘Banjo’ to the chopped up vox samples and breaks of ‘Velocity Funk’, via the ethereal melodies of ‘Heavenly’ and the surging sequences of ‘Warp’, here was a record that proved his techno credentials – if there were still any doubters.

“I had this inspiration in me to make a more instrumental, darker, deeper record and that’s the path I took. You were always getting guys like Derrick and some of the Detroit guys, [saying] like: ‘You ain’t techno, you’re pop.’ So, that probably also pushed me to say: ‘Yeah OK, y’all see I got something here.’”

Saunderson has continued releasing solo music ever since and touring with Inner City. But it was Dantiez who encouraged him to relaunch Inner City with new songs, thanks to another fortuitous moment in the studio, similar to what happened with e-Dancer.

“I found this chord that sounded like Inner City,” Dantiez says. “It was a one hit chord sound, so I took that sound and just started writing, with nothing really in mind, no real vision of where it was going to go. He happened to walk in when I was writing it, obviously liked the song, and from there I think that’s where his head sparked. ‘We should do an Inner City reboot with you on board too.’ We put out that one single, and a year or two after, that’s when we did the show.”

That tune was ‘Good Luck’ and the band performed live with new vocalist Steffanie Christi’an at Detroit’s long-running dance festival Movement in 2017, before releasing a fresh album, ‘We All Move Together’, in 2020. Movement fest is where Dantiez first got intrigued by dance music. Nowadays a prolific producer with releases on labels like Soma, Defected, Nervous and countless others, he can trace his interest back to the first time he visited the Hart Plaza event in the city.

“I remember going to the first or second Movement,” he says. “Just to see the site, the venue, before the festival was even open. And then going to the festival, I had a great time, I was in a dance circle. I went every year since then and I was fortunate enough to play it a few times too. That was the beginning, the intro of me being in the scene.”

There are few better teachers from which to learn dance music production than Kevin Saunderson, but are there ever any familial disagreements or arguments in the studio or on the road?

“We get on for the most part,” Dantiez says. “Obviously there are some edits of stuff that he’ll have in mind for a track that I started collabing on, but I wouldn’t say that we butt heads in the studio too much. It’s special, I don’t think many people can say they can do that. It’s great to always have his feedback on my music.”

Beyond their current project, the future looks bright. There’s more e-Dancer and Inner City music on the way. Dantiez is helming Kevin’s KMS label, putting out singles by both established and upcoming talent. He’s also ready to release fresh tracks with his sibling Damarii under the Saunderson Brothers name. Meanwhile, Kevin is running a new party with his nephew Kweku Saunderson, The Hood Needs House.

“We started to do some of these where it’s more house-related music, a little deeper as well,” he says. “We got that brand out there; people love the shirts and the slogan. We got a showcase coming up soon in Detroit, so we’re engaged with the scene and that’s what we love about doing it.”

As to the future of the Motor City itself, Kevin is hopeful. “We have youth making music,” he says. “There’s more connection because of the internet and social media and most of us are still playing pretty regularly. The scene is always evolving.”

This article first appeared in issue seven of Disco Pogo.

.svg)