The Sabres Of Paradise are on a mission from a dancefloor deity. Their aim? To help secure the legacy of said fallen comrade, Andrew Weatherall. Armed with the re-release of their two studio albums and a series of live dates, Jagz Kooner and Gary Burns reveal all. Why they’ve got the band back together; which vocalists were lined up for the band’s never completed third album and throwing the rule book out of the window. “We didn’t have a plan. It was just make some mad music and enjoy it.” Hit it…

Picture the scene. Millennium Eve. The London Astoria. Onstage ‘The Reverend’ Al Green’s honeyed vocals are gently gliding over a mesmeric motorik-fuelled seven-minute opus that can best be described as electro soul. Buoyed by the fervid atmosphere, Bobby Gillespie rushes from stage left to join in on backing vocals, his gleaming grin indicative of the backstage euphoria. Speaking of offstage, those either waiting to join the throng or who have finished their turn include Tom Waits, Ice T and On-U Sound’s Little Annie.

Also in the wings, watching on as his bandmates bring his studio experiments to vivid life, is Andrew Weatherall. His face betrays a mix of bemusement and pride. ‘How did it come to this?’ his countenance seems to suggest. Chris Cunningham is rushing around filming the gig for a forthcoming documentary telling the incredible story of the 90s most important electronic band. The occasion? The Sabres Of Paradise’s ‘farewell concert appearance’. Acid house’s Last Waltz.

Fast forward 25 years and leaving that ‘vision’ to the parallel universe in which it belongs, the faces of Jagz Kooner and Gary Burns – the other two “studio bods” that comprised the Sabres – are also a mixture of confusion and joy. Sat in Kooner’s studio in Avebury, Wiltshire (“It’s the only studio inside a stone circle on the entire planet,” Kooner smiles, hence the name Stone Circle Studios) it seems the scenario outlined above, wasn’t that far removed from reality.

“After the Sabres imploded, that was it. End of story. Box it all up. Stick it in the archive. Move on,” says the voluble Kooner in short, sharp, staccato-like fashion. Around him and the less vocal Burns are banks of technology, instruments, microphones, wires, records, tapes… lots of neon red lights. “When we started getting the Sabres back together I went into the loft and found a load of DATs of unreleased songs. I found one that said Sabres and Bob G. I asked Gaz if we ever did anything with Bobby Gillespie in the studio. He went: ‘Yeah, we did and it was fucking great.’ I didn’t remember it; at the end it was all a bit hazy. It was imploding, disintegrating, things were falling apart. Got to sort stuff out, move on, get on.”

It’s at this point that the hitherto taciturn Burns pipes up, warming to the memory. The Primal Scream singer was not the only musical luminary that might have appeared on a mooted Sabres third album. “There was talk of that next album having Tom Waits on it. We were going to do a track with Ice T. They were talking about all these people we should collaborate with. Andrew was like: ‘Bloody hell, I don’t want to work with Tom Waits. He’s one of my heroes.’ And then it all got a bit like how are we going to tour this if it’s loads of superstar guests on it? We’ll have to just have a little caricature of them on stage.”

“There was talk of doing something with Al Green,” Kooner interjects, his voice still revealing a sulphurous whiff of disbelief. “These were all the ideas that were coming in from the outside. Record companies, A&Rs… they were all suggesting it. It was like, what the fuck? You know what I mean? We were just a studio band, a production team – me, him and Andrew. We never set out to be in a band.”

We are of course getting slightly ahead of ourselves. To recap: ladies and gentlemen, it can’t have escaped your attention, but The Sabres Of Paradise are most definitely back in the building. Not for a long time. But certainly for a good time. Upon Andrew Weatherall’s untimely death in 2020, getting the Sabres back together was the last thing on Kooner and Burns’ mind. For starters, the pair had lost touch over the years, Weatherall’s passing bringing them back in contact. However, come 2023, Andrew’s brother Ian phoned Kooner with a proposition. It was fast approaching the 30th anniversary of the Sabres’ debut album, ‘Sabresonic’ and Ian wanted to mark the occasion by re-releasing both ‘Sabresonic’ and the band’s second, and final, album – their masterpiece – ‘Haunted Dancehall’.

The ball was rolling. Kooner was then contacted by Martin Brannagan from The Flightpath Estate, the online archive dedicated to Andrew’s extensive creative pursuits. Brannagan asked Kooner if he would take part in a Q&A at one of Weatherall’s spiritual homes, The Golden Lion in Todmorden. He was. So was Burns. This evolved into an additional DJ set, which would incorporate Sabres tunes and their many remixes and production duties too.

“I had a whole week of just deep diving into The Sabres Of Paradise,” recalls Kooner. “I had literally not listened to any of it for 30-odd years. That’s what we did; worked on a piece of music and then moved onto the next thing.”

In Todmorden, Rob Fletcher, another member of The Flightpath Estate and the former promoter of the glorious 90s acidic Manchester night, Herbal Tea Party, also had a request. When the Sabres had played live at the rough and ready New Ardri club in Hulme in 1994, a recording had been made from the front of house desk. Fletcher wanted to know if he could play it before Kooner and Burns took to the stage.

“We said: ‘Of course, cool’,” Kooner says. “So, we’re standing at the side of the stage and they’re playing the live recording from Herbal Tea Party. I said to Gaz: ‘Fucking hell, this is us from 1994. Shit, this sounds really good!’”

“Yeah, it was quite a surprise,” laughs Burns.

And with that came the idea of putting the band back together as a way of promoting the albums. “Because we were actually good,” smiles Kooner. “We had some serious bods with us. Rich Thair on drums, who was also in Red Snapper; Nick Abnett on bass, who was also in The Aloof and Phil Mossman on guitar, who split to New York after and joined this fly-by-night band called LCD Soundsystem. I don’t know what came of them. And then Gary. I mean, the beauty of the Sabres riffs and stuff… it’s all him. Gary came up with all of them parts.”

Enthused by their night at The Golden Lion, the pair approached Thair, Abnett and Mossman to gauge their interest. All were in.

“It had to be done exactly how it was,” says Kooner. “It’s like Four Tops or The Temptations. There’s only one Top left in Four Tops. The other three Tops weren’t even born at the time.”

Naturally, there were doubts. Back in the 90s, the band were only about the present and the future. Their collective sound – an amalgam of wayward post-Balearic dub perfection and electronic futurism – chimed with the spirit of the times, as Kooner acknowledges.

“Every day was Year Zero with Andrew,” he says. “He would be: ‘What we did yesterday doesn’t fucking matter, it’s what we’re doing today. What we do this week is what we’re focusing on. Next week is Year Zero again. We start, it’s a blank canvas, we do something new and you keep moving forward.’ So, like I said, I hadn’t listened to the albums in 30 years because it was all about moving on to the next thing.” He stops. The solemnity heavy in the air. “The problem is, and I spoke to Lizzie (Weatherall’s partner) and Ian about this, we can’t look forward now because there is not going to be anything new. Andrew’s gone and we’re not going to do anything new.

“If Andrew was in the band, from the point of view of playing with the live band, this wouldn’t have happened. The only reason this is happening is because Andrew was happy for the five of us to go and do the gigs. It was brilliant because he used to DJ before and afterwards, but he wasn’t on stage with the band.”

“There was no negativity for me,” says Burns matter-of-factly. “Not after we chatted about it. It just sounded like it could be good fun.”

“That’s partly it as well,” says Kooner. “The last time we did it, it was good fun. It was really hard work, but it was really enjoyable and luckily nobody ended up in rehab. We were all in a good place, but I don’t remember any of it. I think we all came back a little broke, because we took a dealer on the road with us. I think he was the only person that made any money.”

In the timeline of Andrew Weatherall’s ‘career’ – a word he constantly bridled at, preferring the more prosaic, but typically Weatherall-like, ‘job’ – The Sabres Of Paradise were just a brief highlight in a job littered with them. As his star continued to rise after his first flush of fame DJing and remixing the likes of Primal Scream, New Order, The Orb, My Bloody Valentine and James, he began collaborating with Jagz Kooner and Gary Burns from The Aloof. In understated fashion he approached the pair at Flying, Charlie Chester’s infamous acid house soiree, telling them he loved what they did and suggesting they should work together.

“You think it’s the beer talking,” remembers Kooner. “But a few days later he rang me and said: ‘It’s Andrew, I thought I’d chase you after that chat we had. Do you fancy working on a Jah Wobble remix?’ I immediately rang Gary and told him we had to go to Manfred Mann’s studio on the Old Kent Road.”

The success of that remix (‘Visions of You’ featuring Sinead O’Connor) saw the trio establish a prolific production partnership. Every week they’d craft makeovers of tracks for the likes of Galliano and Future Sound Of London, before working on One Dove’s beatific debut album, ‘Morning Dove White’. When they finished work on the Psychic TV track ‘United’, Weatherall proposed they release it under the name The Sabres Of Paradise, thus formalising their collaborative endeavours.

“Was it [the name] from a Haysi Fantayzee B-side or a book about Russian Cossacks?” asks Kooner. “This is debatable. He had the book – about all these good-looking bandits that would ride into town and steal all your gold and women. When you think of the imagery of Sabres – the cross swords, the horse riding, the cavalry coming – that comes more from the book. But in all honesty, I don’t know. We never really spoke about that, but it was one of those things: God damn, that’s a fucking cool name. Yeah, let’s have that.”

Alongside the remixes, the relentless threesome would work on their own stuff off the clock. They soon amassed a body of work that Jeff Barrett, Andrew’s manager, advised them to release. They had the studio – underneath the flightpath estate in Hounslow – the production team, the label, the club… “It wasn’t a corporation, but there was a lot of cross-pollination going on,” explains Kooner.

He continues: “Jeff was inspired by what he was hearing. He loved ‘Theme’, he loved ‘Wilmot’, he loved ‘Smokebelch’, he loved the ideas we were putting together. We’d go into the Heavenly offices and play Jeff a DAT of what we were working on. He would be dancing around the room; that was so infectious and inspiring.”

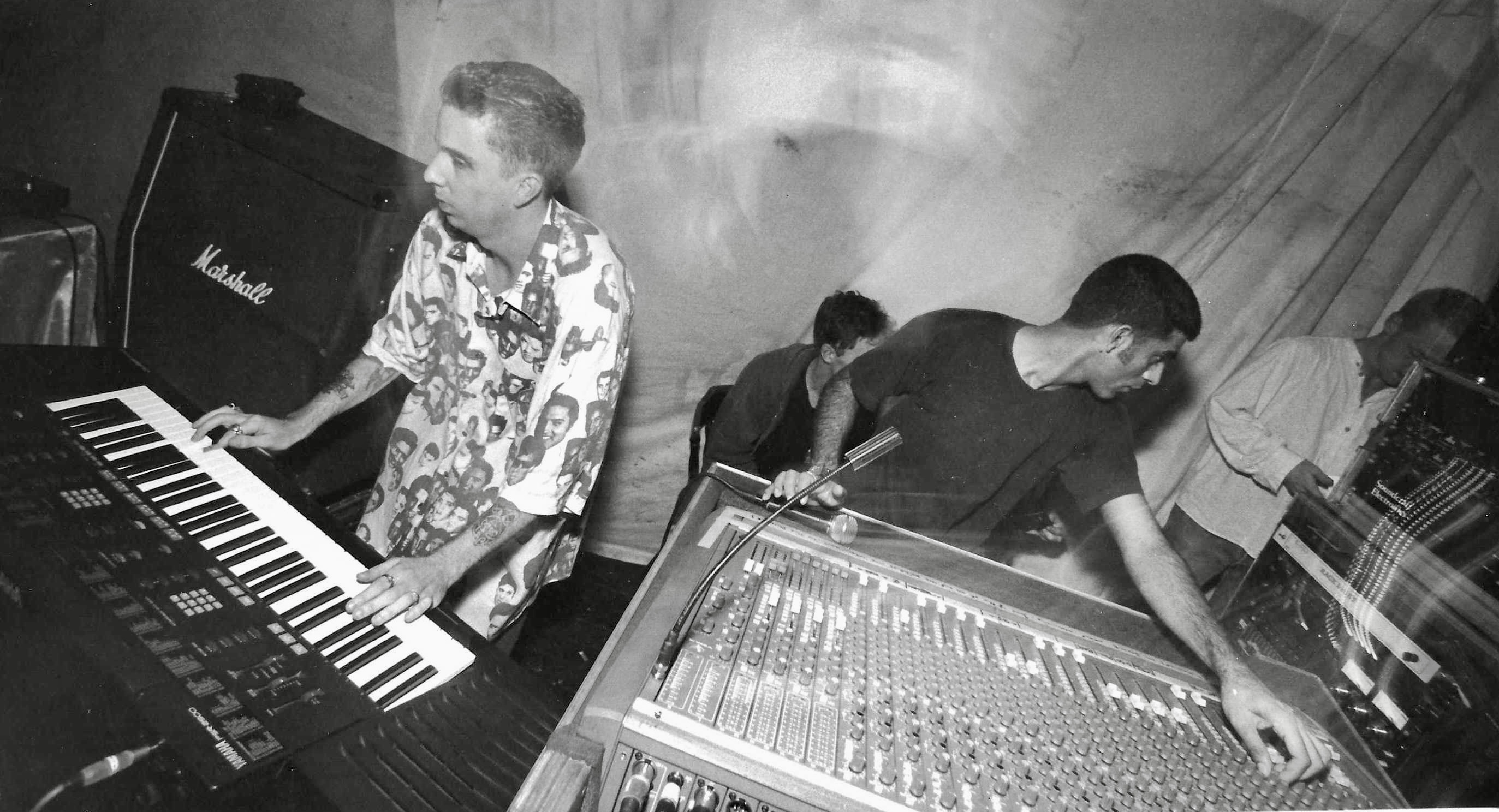

Their debut album, ‘Sabresonic’ was released on Warp in 1993. According to Burns, rather than an album proper, it was a collection of tracks that were sitting on the studio shelf which Andrew would take away, listen to and start to compile. “That’s why to this day I have trouble knowing what some of the tracks are called, because Andrew named them all. When we put them on the shelf, we’d just call it electro track. When it came on the album, Andrew called it ‘Ano Electro (Andante)’, which would be a bit like: ‘Erm, which one is that?’”

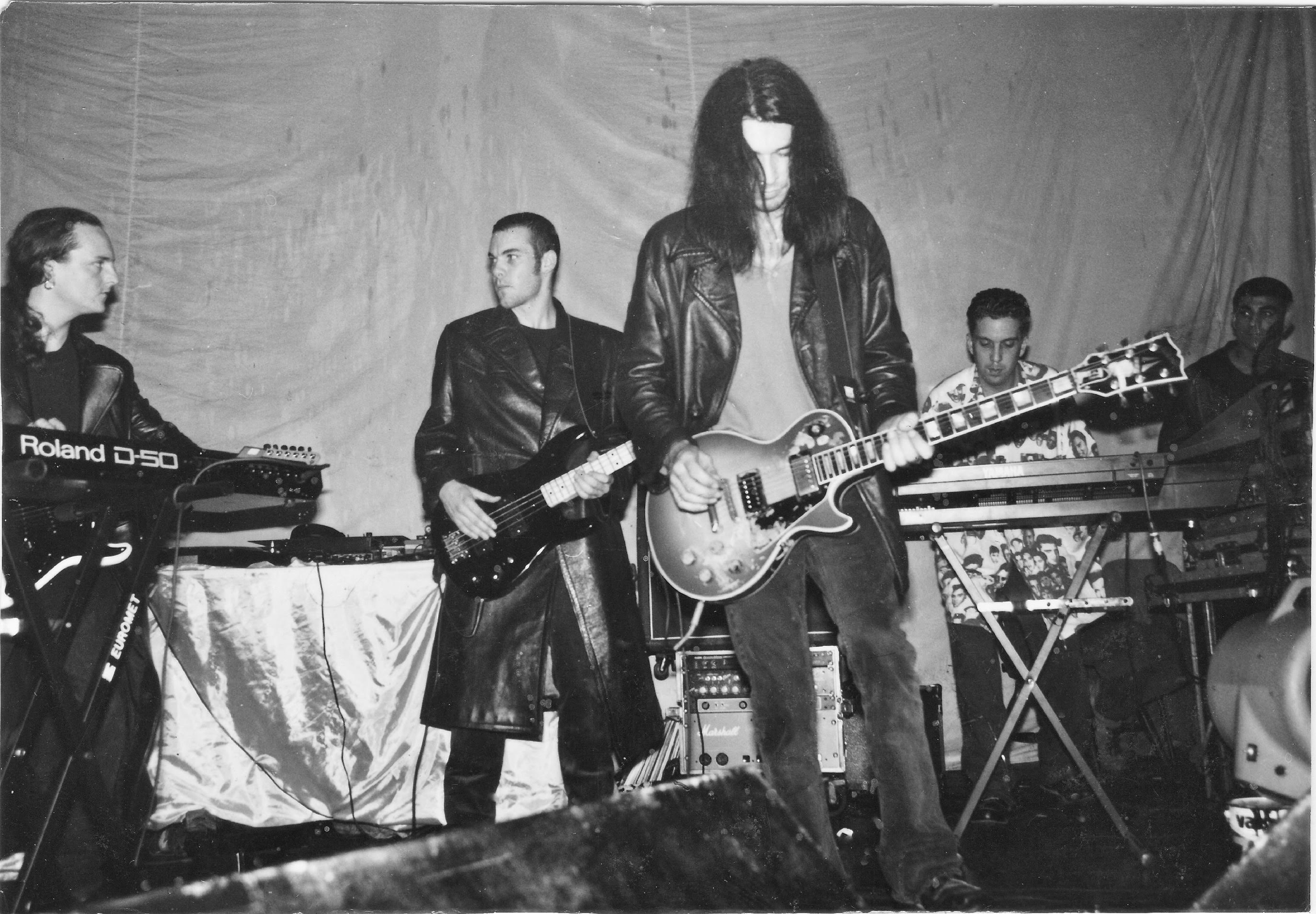

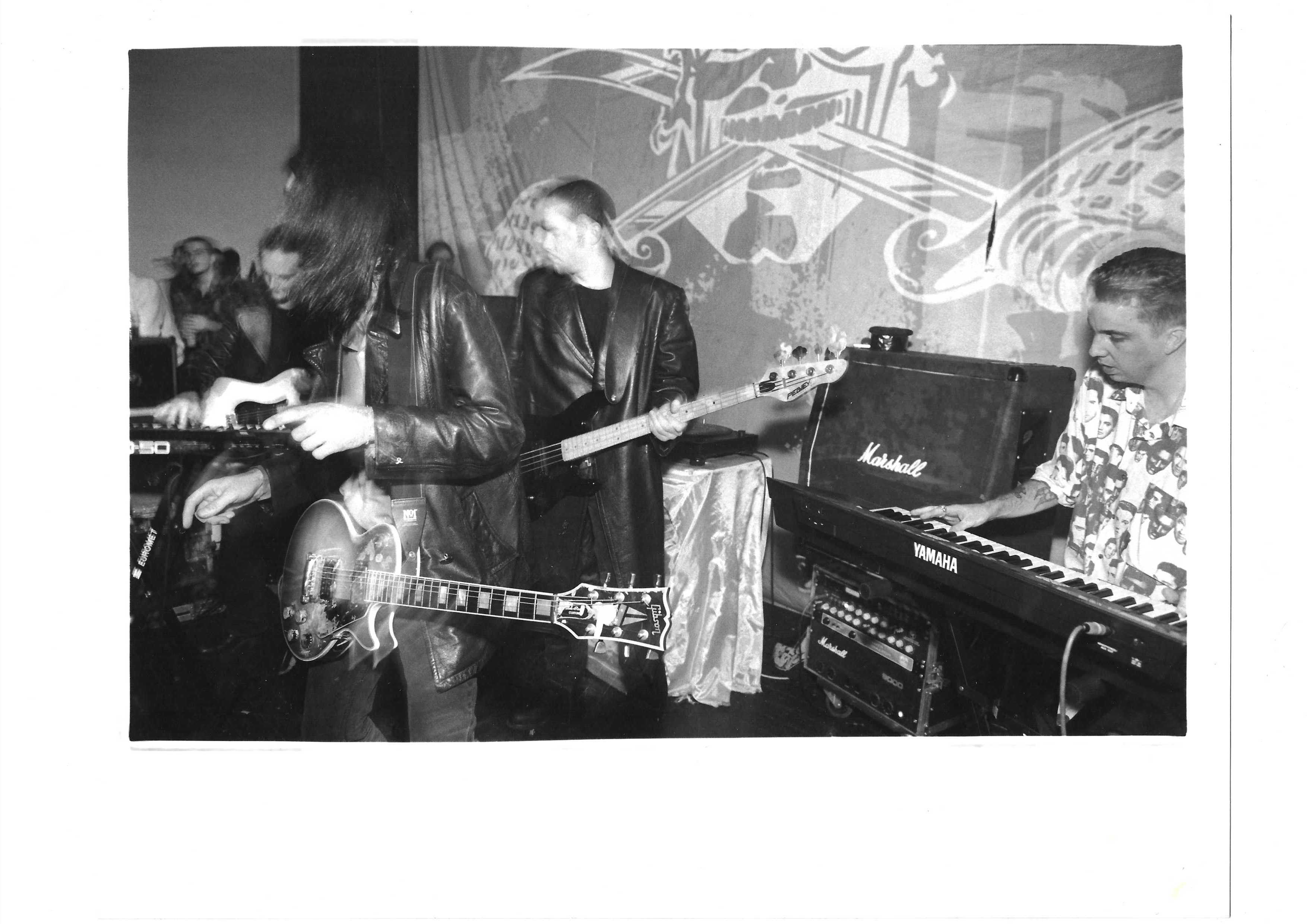

By this point the studio outfit had evolved into a proper band. Their first gig – with Weatherall onstage “triggering off samples, firing off bits and bobs” – was at the YMCA on London’s Tottenham Court Road. They then played at David Holmes’ Sugar Sweet night in Belfast. After that performance, Weatherall came offstage and told the rest he wasn’t comfortable and that they should carry on playing live without him. He would remain in the studio and accompany them on tour as a DJ, which he did on the group’s first tour (alongside one Sean Johnston on merch and Vegetable Vision on visuals). Unlike Paul McCartney, who never got to see the Beatles live, Weatherall did get to witness one of his greatest musical creations.

“It was a great time to be away,” says Kooner. “It was a great bunch of people; we went up and down the country doing gigs and it was brilliant. That’s when we thought: ‘Right, we better take this a bit seriously really.’”

Taking it seriously led to ‘Haunted Dancehall’. The studio band had always experimented, but now they doubled down on their disregard for convention. Weatherall’s Year Zero aesthetic emboldened Kooner and Burns.

“We weren’t interested in traditional songwriting techniques,” says Kooner. “The tried and tested methods. It was throw all that out the window and see what you come up with.”

“We didn’t sit down and have a plan really,” adds Burns. “It was just make some mad music and enjoy it.”

By ‘Haunted Dancehall’ any last remaining inhibitions had gone. Weatherall, Kooner and Burns worked quickly and emphatically. They’d start by flicking through Weatherall’s “incredible record collection” and choosing three pieces of vinyl each. They’d then take those nine records to the studio to see if anything was worth sampling. If it was they’d build up the arrangements on the desk, while Kooner messed around with the effects machines.

“This would then get recorded down to tape,” beams Kooner. “We would then listen back to see if we were happy with it. It’s a bit like the old dub reggae method of building songs.”

One time, the group were in Berwick Street Studios when Ashley Beedle popped in. They wrote three demos that afternoon. “He saw the birth of three songs: ‘Wilmot’, ‘Theme’ and ‘R.S.D.’ (Red Stripe Dub),” Kooner remembers. “It was just beautiful.”

“The stuff we were doing for ‘Haunted Dancehall’… we kind of hit on a bit of a sound,” Kooner reminisces some more. “That kind of metallic dubby sound with interesting melodic hooks and riffs. It was really unique and different. That came from years of experience of being with Andrew and him not giving a shit about what is expected of him anywhere along the line.”

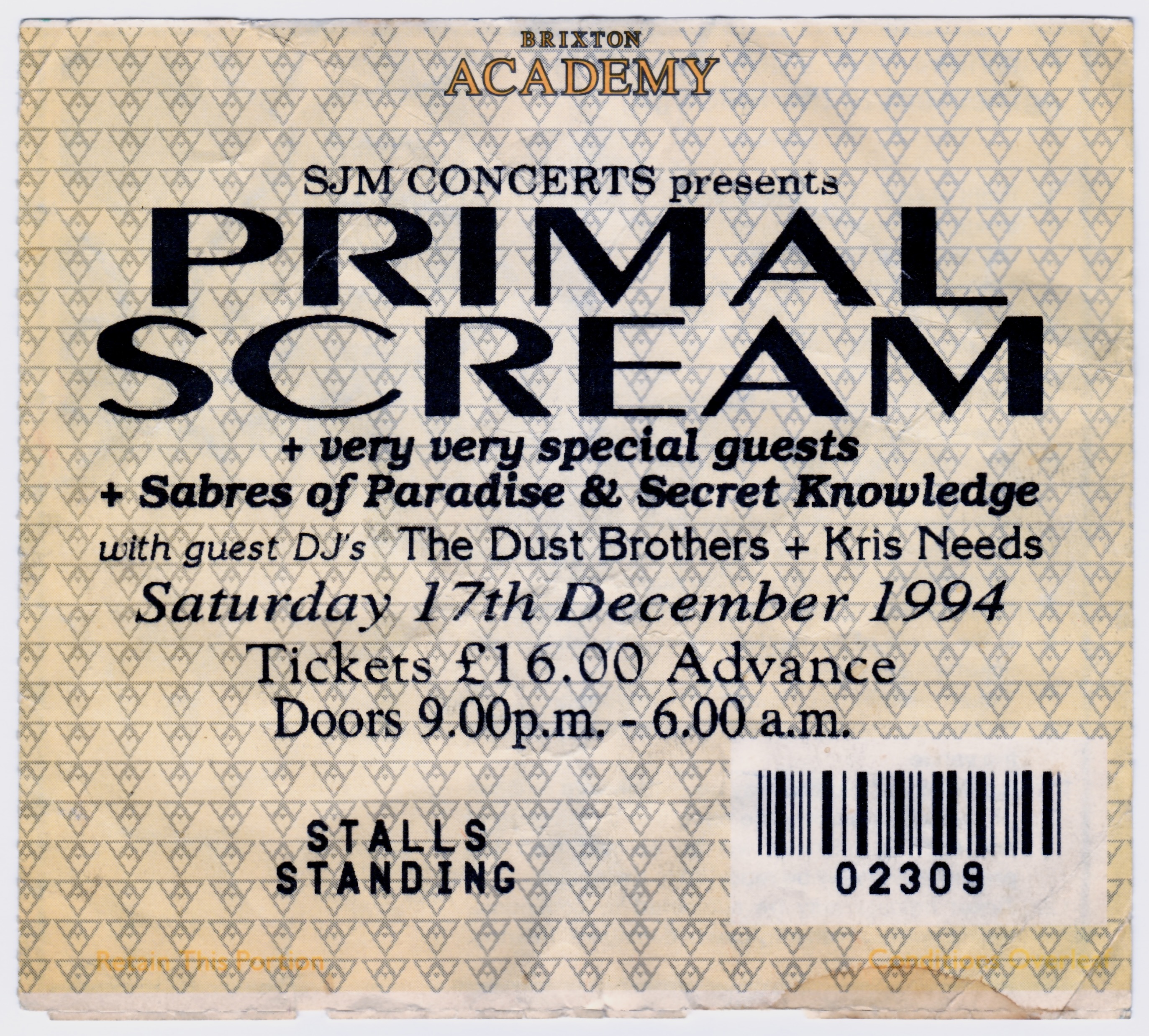

A tour with Primal Scream followed, including one memorable gig at Brixton Academy where, according to Kooner, two records, still unsurpassed, were set – the highest bar take in the upstairs bar and the biggest guest list ever. Oasis wanted them as a support act (“Noel’s a massive dance fan, he wanted us, unfortunately the dates clashed with Primal Scream”) and new songs were started (“We were still in that head space of putting more tunes together and having them on the shelf”), including the recording with Bobby Gillespie and Little Annie.

In 1995, they went on tour to Japan. And that, with a sudden finality, was that. There was no great big fall out. Someone suggested calling it a day and no one seemed to put up too much of a fight. The pair say the details are still vague.

“I can’t put my finger on anything,” recalls Burns. “Still to this day I’m not quite sure what happened there.”

Kooner says a month after the split Weatherall contacted him. He asked Kooner if he thought they’d done the right thing. “I’m like: ‘I don’t know.’ But by that point, it’s typical blokes. Young blokes. You’re not going to go: ‘Do you know what? You broke my heart; we need to have a chat about this.’ It’s just blokes being blokes. ‘It’s done now. Move on.’ It was that kind of mentality. I think we did regret it from that point of view.”

After that brief moment of indecision, Kooner says the subject was never raised again. Kooner and Burns carried on with The Aloof, before Kooner went onto work with Primal Scream on ‘Exterminator’. He would occasionally visit Weatherall and Keith Tenniswood (the Sabres’ former assistant/engineer) in their Scrutton Street studio for tea and biscuits.

“It was all good vibes,” he says. “And then every now and again he’d be DJing somewhere, it was great fun. Years down the line there was no discussion of whether we did the right thing because we were still moving forward. That is what you do as an artist. The only time you can’t do that is when all of a sudden the person that you did do something with is no longer with us. Then it’s a time for reflection. To think about everything that you did, and hold that in a greater kind of regard than you did before. That’s kind of where we are now.”

Where Kooner and Burns are now is busy preparing for this year’s gigs in the mystical sonic stone circle. The old samples, files and technology have all miraculously been brought back to life, unlike, Kooner laughs, when he helped Primal Scream rebuild ‘Screamadelica’ for their comeback shows. “I had a bit of a panic before we started doing this,” he says. “When I was working on ‘Screamadelica’ every piece of kit, every bit of technology we used, every DAT and disc and everything that we tried to load up, either wouldn’t turn on or blew up the instant you ran a bit of electricity through it. So, I had an apprehensive few months of finding stuff and going please play, please load, please don’t fucking blow up. So far we’ve been really lucky. Everything’s loaded up. Everything plays back.” And because it’s 30 years on – and with the advances in technology “and the fact that we’re all better musicians now” – Kooner says the shows will be more impressive.

“We’ll be performing a lot more songs than 30 years ago,” he says. “I can’t tell you which ones yet, as we want it to be a surprise. The songs are developing in a great way as the arrangements are different from some of the versions on the albums – they work better from a live point of view.”

The ultimate goal with this flurry of Sabres activity – the re-release of the remastered ‘Sabresonic’ and ‘Haunted Dancehall’ – and the accompanying live shows, including a gig at fabric at the end of May, is to cement Weatherall’s legacy further. And that of The Sabres Of Paradise.

“Our friends are excited about the shows and that’s great,” Kooner admits. “But you ask a bunch of 20- or 30-year-olds about Sabres and they’re like: ‘Who? Never fucking heard of you.’ So, it’s really a case of ok, you haven’t heard of us, but when you do see us, you will fucking remember us.”

Kooner twitches in his seat one last time at the end of an extensive two-hour chat and smiles, before issuing his final rallying cry. “We’re not coming back for a long time. We are literally going to get the albums out, do some shows, re-establish the name of The Sabres Of Paradise, show everybody what we were like, and then fucking ride off into the sunset again. That’s it.”

The last gang in town are back.

This article originally appeared in issue seven of Disco Pogo.

.svg)