The release of Warp’s ground-breaking ‘Artificial Intelligence’ compilation in 1992 was a watershed moment for electronic music. Not only did it help turn on a new generation of listeners to electronica, it went some way to legitimising the sounds to a reactionary, indie-obsessed music press. Sherman should know, he was pushing dance music while ‘at the controls’ at the NME. He looks back at this pivotal release, and examines its significance today…

It’s not going to be long before an artist can make an album, film, CDI and CDO in his or her own bedroom for a few thousand pounds, advertise the ‘product’ to hundreds of thousands of people directly via the computer networks and sell directly to them. This will completely cut out the need for the usual trek around the major entertainment companies looking for finance and could lead to things getting really interesting.

Extract from the original 1992 press release for ‘Artificial Intelligence’

Speeding out of the late-80s and into the 90s, new technology was enabling musical fences to be frequently smashed down. Electronic music had been on the rise since acid house (and the acid) had kicked in and now it was splintering off in new directions as it bleeped and sub-bass-ed its way out of bedrooms across the country. With a few basic machines you could make music in a brand new way, create brand new sounds and beats that inspired brand new ideas, the results of which flooded into the record shops weekly.

This science of samplers, sequencers and computers, linked together with drum machines, synths and whatever else you could find, allowed producers the ability to produce their own final product without having to go through the usual artistically restrictive filters. Welcome to the future.

I was manning the controls of NME’s dance section at a time when dance music was first sweeping across the country. The paper was still a powerful force in British music and had become pretty much a full-on indie-paper covering Morrissey’s every breath, so it was really hard to get electronic and dance music taken seriously despite electronic pioneers New Order being regulars on the cover, Madchester and the genre-splitting ‘Screamadelica’.

Dance music was making its way across Europe as the underground bubbled overground, but if it wasn’t on Creation it was usually seen as throwaway club music lacking authenticity by a lot of journos at the inky weeklies. I wasn’t a trained journalist, I was the editorial assistant who was just really into the music and who kept moaning to editor Danny Kelly that the paper wasn’t covering the real action. I fell into it all by accident really because I knew about the records and what was going on in a world that most of the paper was oblivious to.

It seems crazy now thinking back to how it was, but ‘dance’ music was rather sneered at by segments of the industry early on – there would often be comments about only having to press a few buttons to make the music. At the paper, one staff writer, an ardent Nick Lowe fan, thought it hilarious to dance around me going ‘bleep, bleep, bleep, bleep’, and at one point I was ‘temporarily suspended’ from constantly playing tunes on the office hi-fi. Prior to forming The Dust (later Chemical) Brothers, Tom Rowlands’ Ariel visited techno towers to play me their single ‘Rollercoaster’. They were adamant they couldn’t leave me their only copy but eventually had to because of my ‘blocked status’ on the stereo. Tom, I still have your record.

So it became a bit of a crusade as I genuinely thought it was scandalous that so much great music was being ignored. ‘Artificial Intelligence’ would be among the records that helped change minds and mark a new era.

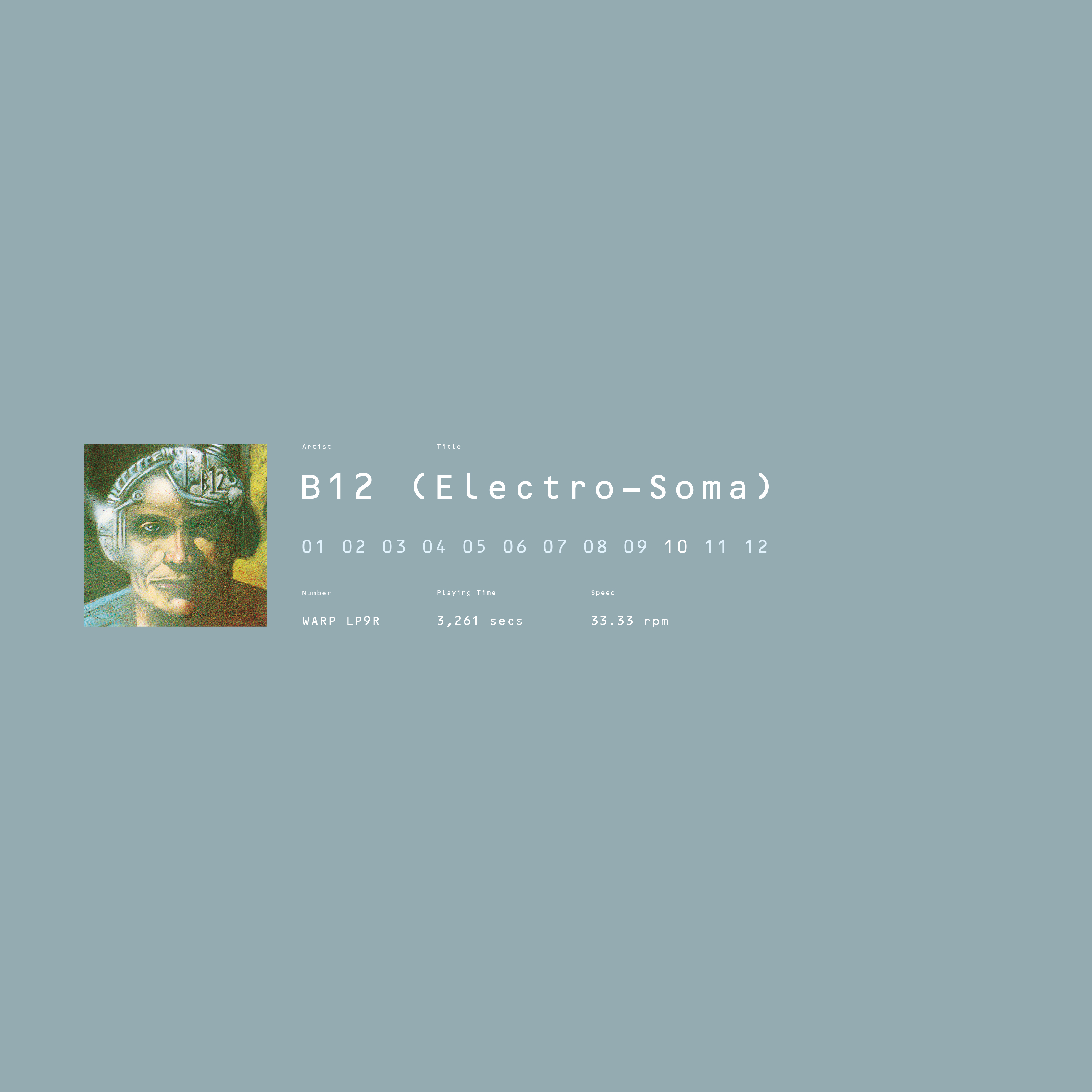

Occasionally the odd sign would appear that hinted towards new offshoots for techno. ‘Altair IV.1’ by States of Mind on Plus 8, along with two 12s by the unknown Infamix – later to morph into B12 – being early markers in 1990. The release of The Orb’s first post-clubbing chillout album, ‘Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld’, in April 1991, helped slow everything down and space everything out, designed, as it was, to be consumed in one piece. Later that year Network put out the brilliant ‘Mood Set’ EP by Xon; an atmospheric trio of tracks that shuffled and skittered with a deep mechanical funk that was more for the mind than the body, so I described it as ‘armchair techno’ in my review.

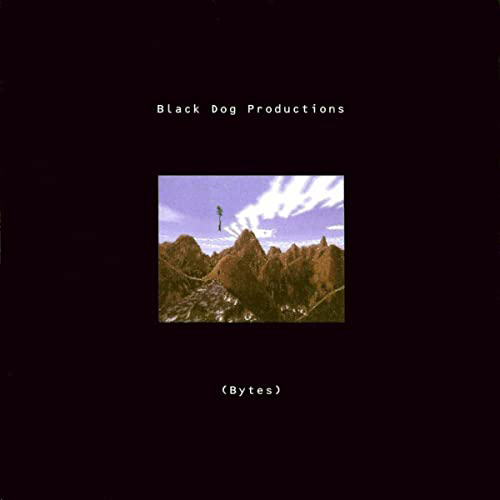

The Black Dog and Irdial Discs had been working in a different dimension for a couple of years and there wasn’t really a genre that could hold them. True to form, Cabaret Voltaire were posted on the frontline, their ‘Body and Soul’ album and EP releases ‘Colours’ and ‘Easy Life’ being among those remote viewing the future. In the autumn of 1991, Aphex Twin released his first single ‘Analogue Bubblebath’. It was played by both Colin Dale and Colin Faver on London’s Kiss FM, both of whom had a huge listenership regularly tuning in to hear the latest imports from labels like Djax-Up-Beats, Eevo Lute, Planet E, Underground Resistance, Transmat, Metroplex, all spun alongside new British labels like GPR, Radioactive Lamb, Rephlex and the cityscape cinematics of B12, who hailed from Barking in Essex, but shrink-wrapped their releases to appear Detroitian.

Out of all this a new kind of hybrid techno was emerging, one that wasn’t really for clubs and which wasn’t just ambient but balanced somewhere in-between. It was more textured and organic, sometimes slower in pace, sometimes more abstract and it explored new structures. It was miles away from the clattering breakbeats and hoover noises of rave and revolted against the quick turnaround and disposability of the white label fashion. Independent of each other, all these people had tuned into the same wavelength and were all now speaking a new electrical language.

“There was no ‘scene’ as such,” says Steve Rutter, who, alongside Mike Golding, was making futuristic techno influenced by the first Detroit wave of producers and releasing it on their own B12 label run from a fax machine behind Rutter’s sofa. “It didn’t exist. As we went on we hooked up with Steve Stasis and Kirk Degiorgio and that was it for our little group that liked this music. Four of us!”

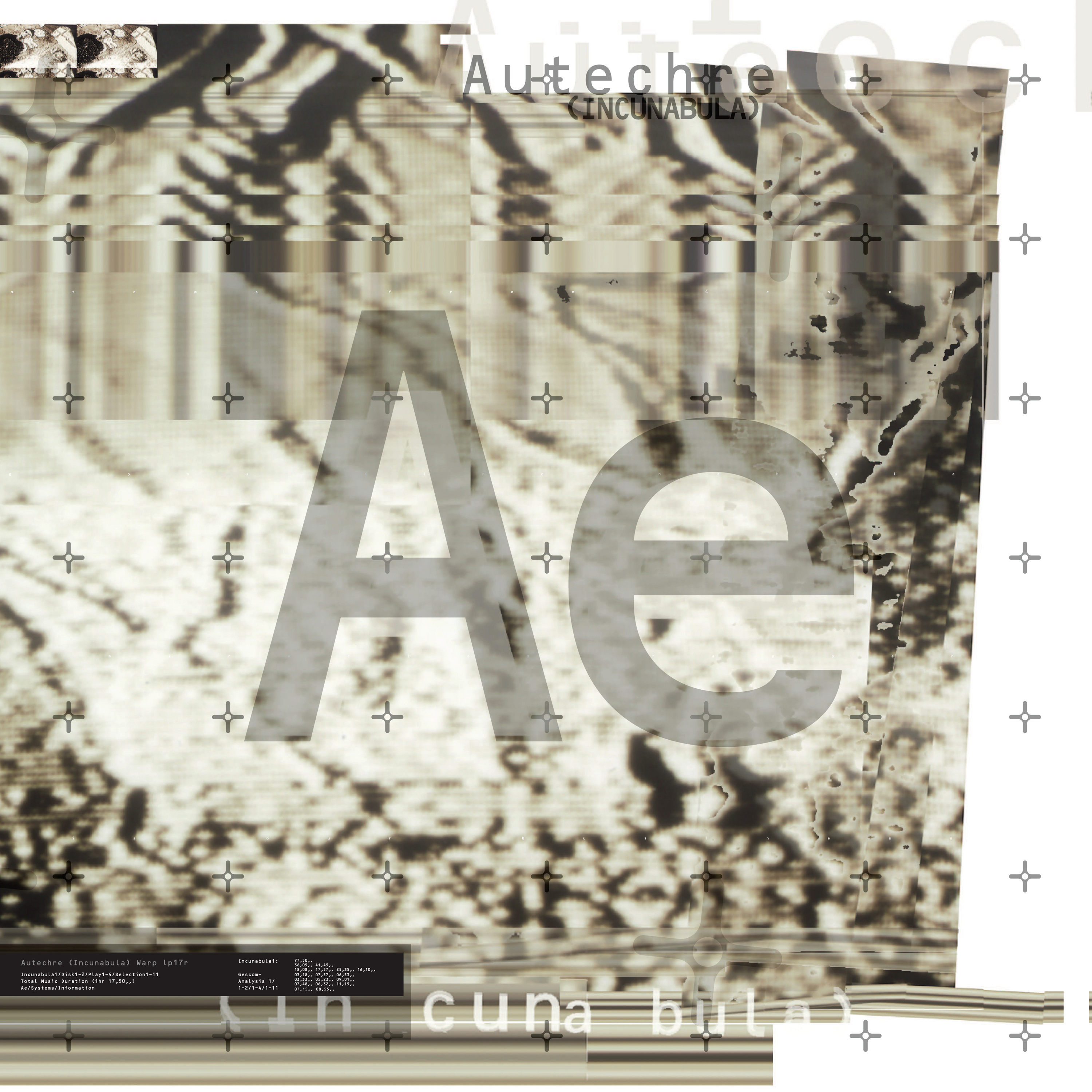

Autechre’s Sean Booth and Rob Brown also felt out on their own as, “Warp didn’t really get our music initially.” They’d been sending tapes to the label for two years only to receive standard record company rejection letters in return. It took a combination of LFO’s Mark Bell hearing an Autechre demo tape playing in the Warp office and telling them they should put it out, and Booth ringing label co-owner Steve Beckett and asking: “Why the fuck aren’t you listening to our tapes?” for the label to pay attention. Like most electronic labels at the time, Warp were driven by 12-inch singles directed mainly at clubs with perhaps the odd track that didn’t quite fit the dancefloor making its way onto a B-side. The concept of the ‘dance’ album hadn’t fully taken off yet.

Essential to the ‘Artificial Intelligence’ story was the opening of Fat Cat record shop in London’s Covent Garden in 1991. If you lived in the capital and were into techno and electronica, inevitably you would discover this one-stop shop for all your drum-machine related needs. The racks of the small basement space in Monmouth Street would be filled with fresh releases coming in from the States, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium and across the UK.

It could only squeeze ten or so people in at best and on Fridays and Saturdays it could get so rammed you’d have to overflow into the even tinier office where you might get into a chat with Tony Thorpe and Neuropolitique’s Matt Cogger. Those who couldn’t get into the actual shop would line the stairs yelling down for the records they wanted as they were played. Björk would regularly visit, Kevin Saunderson would be in, Andrew Weatherall, Alistair Cooke from Back 2 Basics, Infonet’s Chris Abbott, Colin Dale, Richard D. James... It played a key role in the development of UK techno and electronica, acting as a hub and a meeting point for many of those active in this slowly building movement.

“Without knowing it we created a space for that community to connect with each other and realise they weren’t isolated,” co-founder Alex Knight recalls. “We felt that we were on our own initially, we had no idea that there was all this other stuff happening until we opened in Monmouth Street. Ed from The Black Dog came down within the first couple of months of us opening and said that his distributor was going to melt down all of his unsold records and could we sell some? We said: ‘Yeah, we can probably sell the whole lot!’ That was one of our earliest connections to that scene.”

Along with The Black Dog, the B12 boys and Akin from Irdial, Grant Wilson-Claridge of Rephlex would turn up with a box of records on the label he had started with Aphex Twin, and which they had tagged ‘Braindance’ as a reference to the music’s psychedelic qualities.

“You’d have people dropping cassettes in for us to pass onto labels like Rephlex,” says Knight, “and then Grant would come down with a new release by the kid who gave you a cassette a few days earlier. So it felt really organic. Everything felt brand new and every week you’d get surprised by something that blew your mind.”

In January 1992 there was a breakthrough when I managed to convince the paper to do a techno issue. The closest NME had come to a dance cover was nearly two years previously when it flirted with the idea of showcasing Andrew Weatherall at the time of his James remix of ‘Come Home’, but the outraged Power-Pop Police soon blocked this rebellious notion.

However, following LFO’s success the previous year, including a pause-button moment when they had appeared on ‘Top of the Pops’ with their debut single constructed from Morse code bleeps, electro rhythms and warehouse rattling sub-bass, it was decided they would grace the front page. But when the photos appeared and Mark Bell and Gez Varley were posing with burning guitars, it felt a bit gimmicky, like the paper was portraying some sort of confrontation between dance and indie when the reality was nothing like that at all. But hey, it was a leap forward. LFO were on the cover. Techno was on the cover of the NME. This was major, and it became a massive talking point.

Dave Balfe, once of the mighty Teardrop Explodes and now owner of Food records (Blur/Jesus Jones), rang editor Danny Kelly and demanded that he sack me! Red from laughing, Danny waved me into his office to listen in while Balfe, who was apoplectic on the other end of the phone, ranted something about me being a really bad influence at a musical institution and that the NME was no place for dance music. ‘Off with his head!’. Just another day at the office.

There were definitely a few at the paper who appreciated dance music and some would go to clubs, but generally the ‘world’s biggest selling music weekly’ couldn’t handle the ‘Faceless Techno Bollocks’ of it all. It didn’t understand it and was therefore a bit nervous of it. For me though, it was this element of anonymity that was the music’s great leveller. It didn’t have to play by the rules of the rock industry. Thousands of working class kids were going raving in clubs, warehouses and fields every single weekend. There was a fast output of records that came and went and often included little or no information about who made the music. And what the artists looked like wasn’t that important because the people making it didn’t want to be pop stars or on TV.

Throughout early ’92 more labels began to appear like beacons on the horizon: Evolution, set up by Tom Middleton and Mark Pritchard of Global Communication, Applied Rhythmic Technology (ART), Rephlex, Infonet and Radioactive Lamb. Alongside artists like Neuropolitique, Kirk Degiorgio and In Sync, there was a wealth of music created that was becoming more complex, expressive, filmic and diverse. It only needed a jolt to bring everything into focus. Steve Rutter remembers the moment it did.

“One day a fax came through which said something like: ‘We’re having a meeting for electronic music people.’ There were some names of who were invited – A Guy Called Gerald, Cabaret Voltaire. The Black Dog were invited. I think Kirk was there.”

That meeting of futurists in a Shepherd’s Bush pub in early 1992, was a pivotal moment in the development of ‘Artificial Intelligence’ and the kinetic effect it would have on electronic music as a whole. The time was right, Steve Beckett and Rob Mitchell recognised it and planned to make Warp synonymous with electronica.

Rutter continues: “They’d reached out to everyone, but we didn’t know who was behind it or what it was. I can’t remember if it even said Warp on the fax. But they did it. They had an idea that this electronic thing was going to be big. They were really clued up, especially Rob, he saw something which none of us really did. He was clued up in the art of the possible.”

Sean Booth also recalls sensing pressure in the air. “There was common ground there because we all knew this was already a thing. So they felt comfortable doing ‘Artificial Intelligence’ because they knew they were plugging into something that was really real. Dance music was out of context, people were listening to it at home, but that wasn’t weird, we’d grown up listening to dance music on Walkmans and boom boxes. We were too young to go to clubs so the whole listening to electronic music in isolation was dead familiar to us already, even before the rave scene.”

The release of ‘Artificial Intelligence’ in July 1992 was a future shock; the spark that ignited, and united, this new movement of electronic artists. Warp had been on the bleep and bass trail for the previous two years, but this album collected the music into a new futurist manifesto. As a concept, it demonstrated to a wider audience that the machines were just tools people were using to follow their feelings, that they could be used to create as much emotion in this music as in any other.

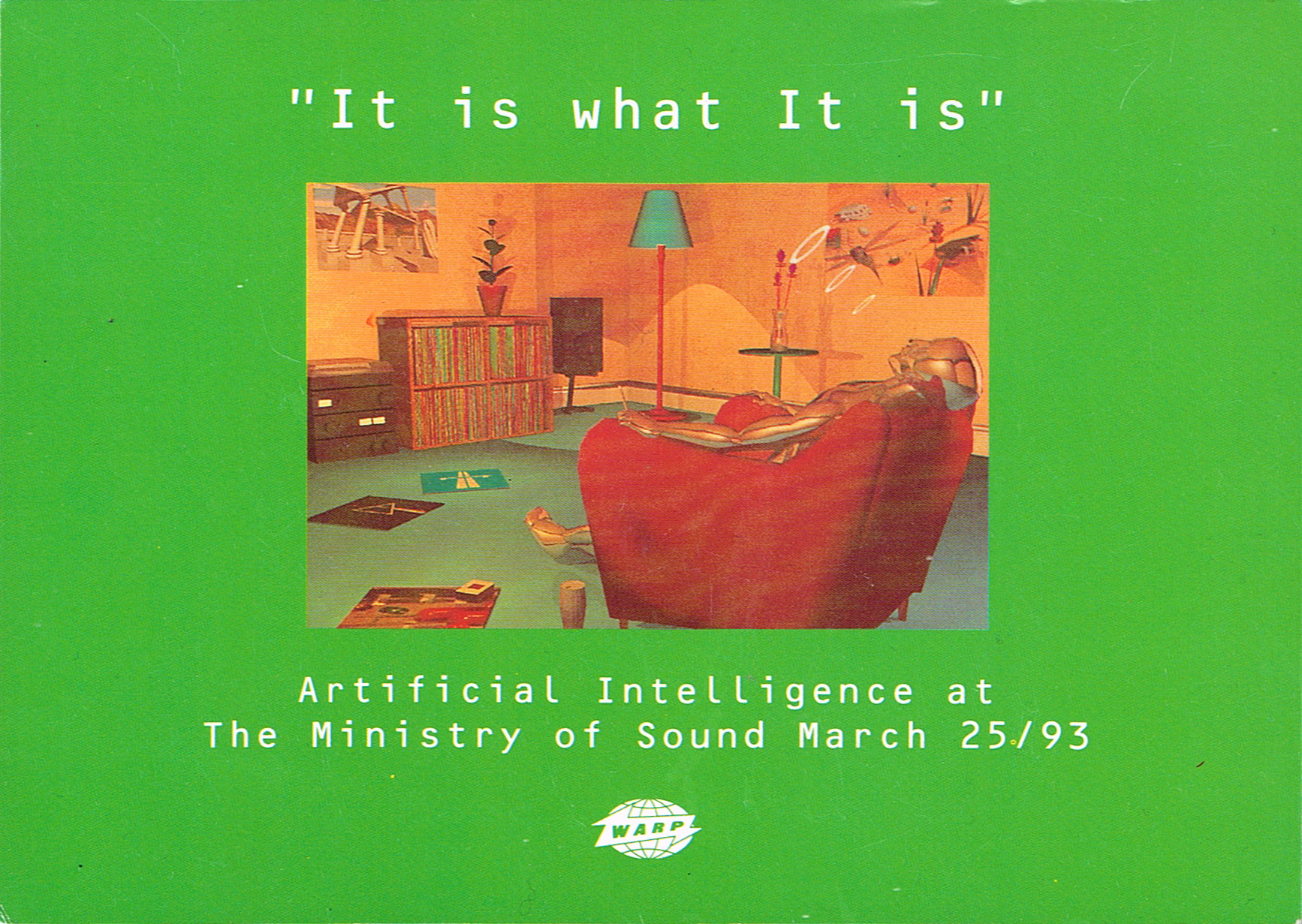

For the uninitiated, it acted as a portal into this new digital world of pictorial instrumentals, introducing Autechre, The Black Dog (I.A.O.), Aphex Twin (The Dice Man), B12 (Musicology), Richie Hawtin (UP!), Speedy J and Alex Paterson to a much broader audience. And even though the music was mostly made by British artists, it turned a lot of people onto the sort of spacious, Detroit-led sounds that a lot of deeper techno was built on. But to counter the often deadpan sci-fi side of the music, the tongue-in-cheek sleeve featured a cyborg reclining in an armchair, spliff on, letting go to the sounds of Kraftwerk, Pink Floyd and the first Warp compilation ‘Pioneers of the Hypnotic Groove’.

The original sleeve was conceived with The Designers Republic, a name now twinned with Warp. Its co-founder Ian Anderson, a self-taught graphic designer, remembers how the sleeve needed to convey the sense that it was listening music.

“Because electronic music was intrinsic to everything we were doing,” he explains, “everything about the image is saying when you get home, this is what you chill out to. That there’s enough in this music to listen to. There was a lot of talk at the time about heritage and where it was all coming from. At that point there weren’t many reference points so people looked back to things like Pink Floyd and Kraftwerk, kind of a stoner thing and for student bedsits. I liked the idea at the time although it wasn’t something we really loved, but in hindsight I really like it and I think it’s really iconic now.”

The album marked a shift in perspective in the music press as the connections with Kraftwerk and Floyd enhanced the realisation that this was a home listening experience. Once they recognised that students were getting heavily into electronic music, they had to pay more attention. Basically, ‘Artificial Intelligence’ justified some of my rantings in the NME office.

“We didn’t have much idea that other people were making this music until the album came out.” explains Booth. “We were listening to a lot of Black music like hip hop, Juan Atkins and people like Smith & Mighty, Unique 3 and Arthur Baker. We were heavily into electro and just saw our music as a linear continuation of it, so when we heard it we thought it was mostly inspired by electro and was just a further development.”

Steve Rutter remembers being unsure about the album at first. It didn’t connect immediately.

“When me and Mike first heard it I don’t think we necessarily thought all of it belonged together. Our music at the time was just us trying to copy Transmat and Detroit techno, whereas the other guys on the album were doing something a bit different. I wasn’t sure that it all fitted together. I thought it was a thing of beauty, but I didn’t really understand what was going on because I thought for a long time that our music wasn’t really anything, it was just what we did because we liked it.”

Down at Fat Cat, the album became a best seller. “We sold the album for years and continued to sell it because it became one of those classic albums that everybody wanted,” says Alex Knight. “A lot of the people on that record were in the shop all the time and were friends of ours so it always got pushed. We felt proud because it felt like our little community on that record. I feel privileged to have been part of that.”

The attention ‘Artificial Intelligence’ brought to electronica and the confidence it now gave other artists and labels to plan full albums, was furthered at the end of the year by the release of Aphex Twin’s seminal ‘Selected Ambient Works 85-92’ on R&S. It sounded utterly different to anything else. This was partly enabled by Richard D. James’ penchant for stripping back bits of equipment to improve them, soldering in new components and removing others in the vein of experimentalists like Throbbing Gristle and King Tubby to create unique sounds from customised machines. The rock press gradually embraced James for his entertaining and lurid tales more than his skills as an electrician; that he lived in a bank with a recording studio in the vault, that he owned and drove a tank, pulled songs from lucid dreams, once played a show using sandpaper and a blender, that he was paid four grand to remix alt-rockers The Lemonheads but didn’t bother listening to the original and instead returned one of his own old tracks which was then not released. Some were possibly true and some maybe not. Possibly maybe. We should hope the mystery of the Aphex Twin remains eternally unsolved.

Throughout 1993 electronic music exploded and seemed to shapeshift weekly. New artists, labels and clubs sprung up and as more electronic acts began to play live, nights like London’s Megadog, Manchester’s Herbal Tea Party and Birmingham’s Oscillate put on events where DJ sets melded into live performances and back again and where the visual side was often equally important. Clubbers flocked to see all these new artists like Aphex Twin, The Black Dog, Autechre, Psychick Warriors Ov Gaia, B12, Higher Intelligence Agency, Orbital, Sun Electric, Biosphere, Ultramarine and countless others who were all now out on the road.

The founder of Herbal Tea Party, Rob Fletcher, recalls the initial difficulty in tracking down all these new artists and DJs. “I would basically look on the back of sleeves or get phone numbers off labels to ring artists or agents. I’d go to clubs to meet people then hang around the booth at the end of the night to talk to DJs. I didn’t really see electronica as a separate genre. I just saw a massive amount of leftfield dance music whether it was ambient, Detroit or progressive. Techno was a broader word back then before it started going into very defined, separate genres.”

The crowds would often comprise the spectrum of night people. “It was a total mish-mash” Fletcher says. “You’d get ravers, people from the festival scene, scallies, students, clubbers who also went to The Haçienda. It was a total mix and I wanted the vibe to be like that, loads of different music and people coming together.”

Sean Booth also remembers a time when dance music was a uniting force. “In the early-90s it was a global thing and all about being together. The whole techno scene was a global phenomenon from Detroit to Europe to Japan. Everyone was friends. No one remembers any of that now.”

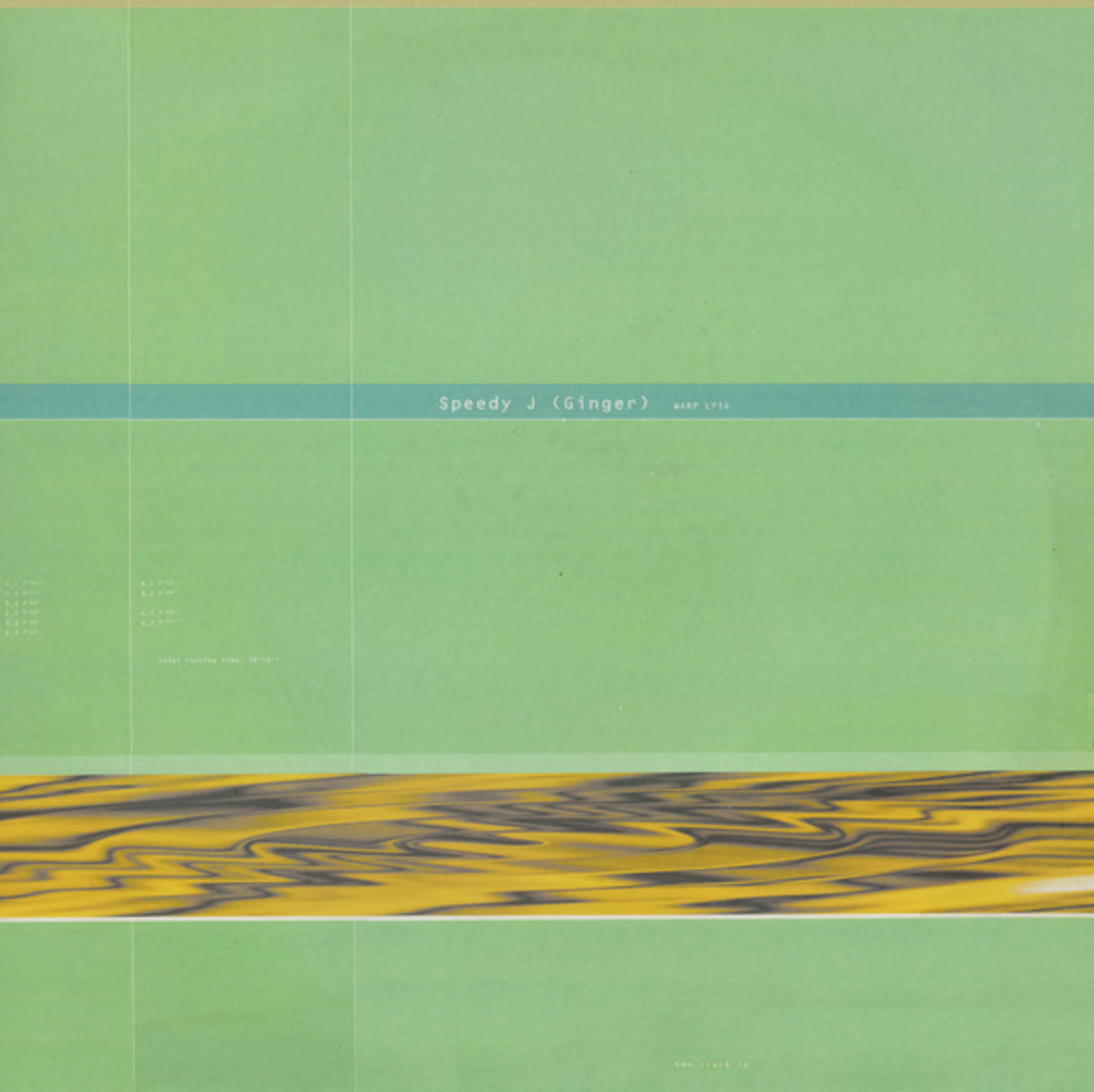

The album itself also went onto birth a series of releases under the Artificial Intelligence umbrella – these included Polygon Window’s ‘Surfing on Sine Waves’ (another Aphex alter ego); Richie Hawtin’s ‘Dimension Intrusion’ (released under his F.U.S.E. pseudonym) and Speedy J’s ‘Ginger’. The final release came in 1994, with the ‘Artificial Intelligence II’ compilation bookending the series perfectly.

Techno and electronica was beginning to spread and would ultimately become an integral part of some of the major festivals. When The Orb headlined the NME Stage on a special Saturday night at Glastonbury in 1993, so many people wanted to be part of the experience that the gates had to be shut and the field locked down. When new press darlings Suede had headlined the same stage on the Friday, it looked like a fan club turnout. Orbital carried on the task the following year to push techno home at Glastonbury and in 1995 the festival pitched up a dedicated dance tent. Now it’s a whole Dance Village.

And so, 30 years on and the past’s future is now the present. ‘Artificial Intelligence’ has more than stood the test of time but, equally, so has much of that early techno and electronica which captured the energy, dynamics and freshness of the period. All the other artists, labels, shops, clubs and DJs are of equal importance to the story of ‘Artificial Intelligence’ because that early scene is where the album was born. The effect it caused on subsequent next-step artists such as Photek, Björk, Squarepusher, Andrea Parker, Boards of Canada, Two Lone Swordsmen, Riz Maslen and thousands of others, was quickly noticeable.

It wired itself into dubstep, indie, drum’n’bass, hip hop and beyond. Today you can trace it deep into Bovaflux, on some of Paul Woolford’s Special Request albums and there’s continuance in some of the sounds Billie Eilish uses. Electronica doesn’t stand still and the music continues to evolve and shift and influence and be influenced. This is evident today with Autechre, Black Dog, Aphex Twin, Richie Hawtin, Steve Rutter and Alex Paterson all still pushing at the musical frontiers that new technology perpetually enables.

But technology also dates. The original artwork was created with now redundant graphics tools, so when Warp went to retrieve the artwork in preparation for re-scanning ahead of the album’s re-release, they found all physical copies of the LP and CD were missing. It appears they were borrowed or ‘liberated’ somewhere down the line by either an intern or a leaving staff member who was missing this particular required listening. At least they had good taste. Messages went out along back-channels for anyone with a decent copy they could loan. My copy was too battered, but I managed to locate one from an old friend, one Alan Gray, once a founding member of Glasgow’s infamous Rubadub record shop (still a lighthouse for electronica in Scotland), but now head of the Scottish chapter of ALFOS. Stand up Sir Alan, you have helped resolve Warp’s sticky artwork predicament, as it’s known in the trade.

Now, for 30 years I’ve often wondered about the cyborg in the armchair and whether it related directly back to my description of the Xon record. I might be about to discover the answer. Surely someone must have re-used the phrase at the planning stage? Ian Anderson laughs, he isn’t sure if ‘armchair techno’ was a specific detail to the brief, but he does tell me that the designer who worked on most of the artwork was a Grateful Dead stoner. Ouch. Thirty years, own myth shattered!

It would have been great to speak with Steve Beckett again but having moved on from Warp long ago he politely declined an interview. Although I was forwarded a message from him saying: “Just send them what Midjourney AI came up with (in 45 seconds) asking it to imagine ‘Artificial Intelligence 3’ LP :).” With it was enclosed an image produced by an artificial intelligence app.

I rather like the fact that Steve replied with such uncluttered minimalism. That, my friends, is ‘Faceless Techno Bollocks’ for you.

This article first appeared in issue two of Disco Pogo.

.svg)