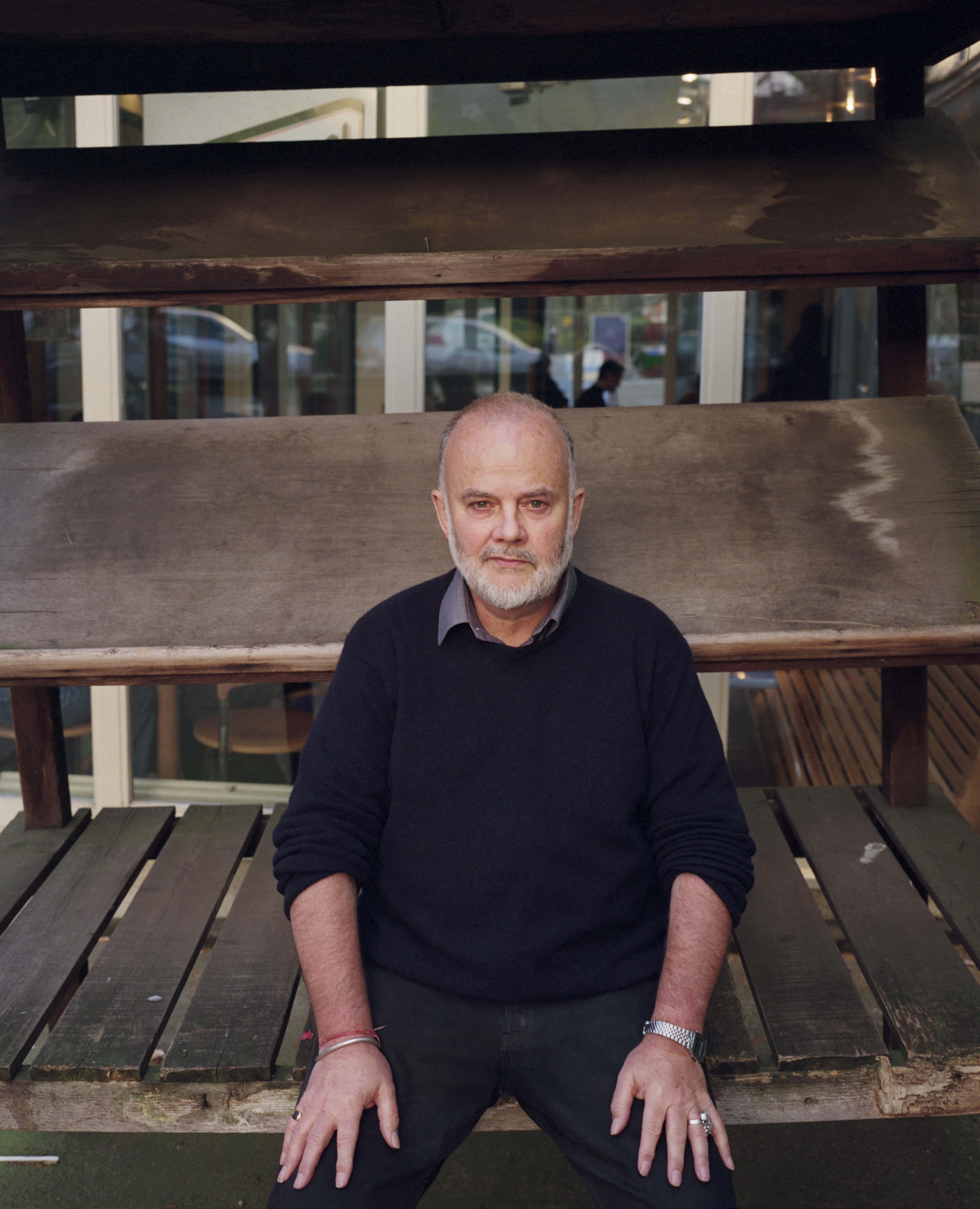

Featuring tears, tantrums and ‘Teenage Kicks’, this is the behind-the-scenes story of John Peel’s unforgettable fabric mix, as witnessed by the legendary broadcaster’s friend: former Fabric employee and Jockey Slut journalist Nick Doherty. A friend of whom Peel once knowingly enquired: “Are you actually doing anything there or just trying to look cool?”

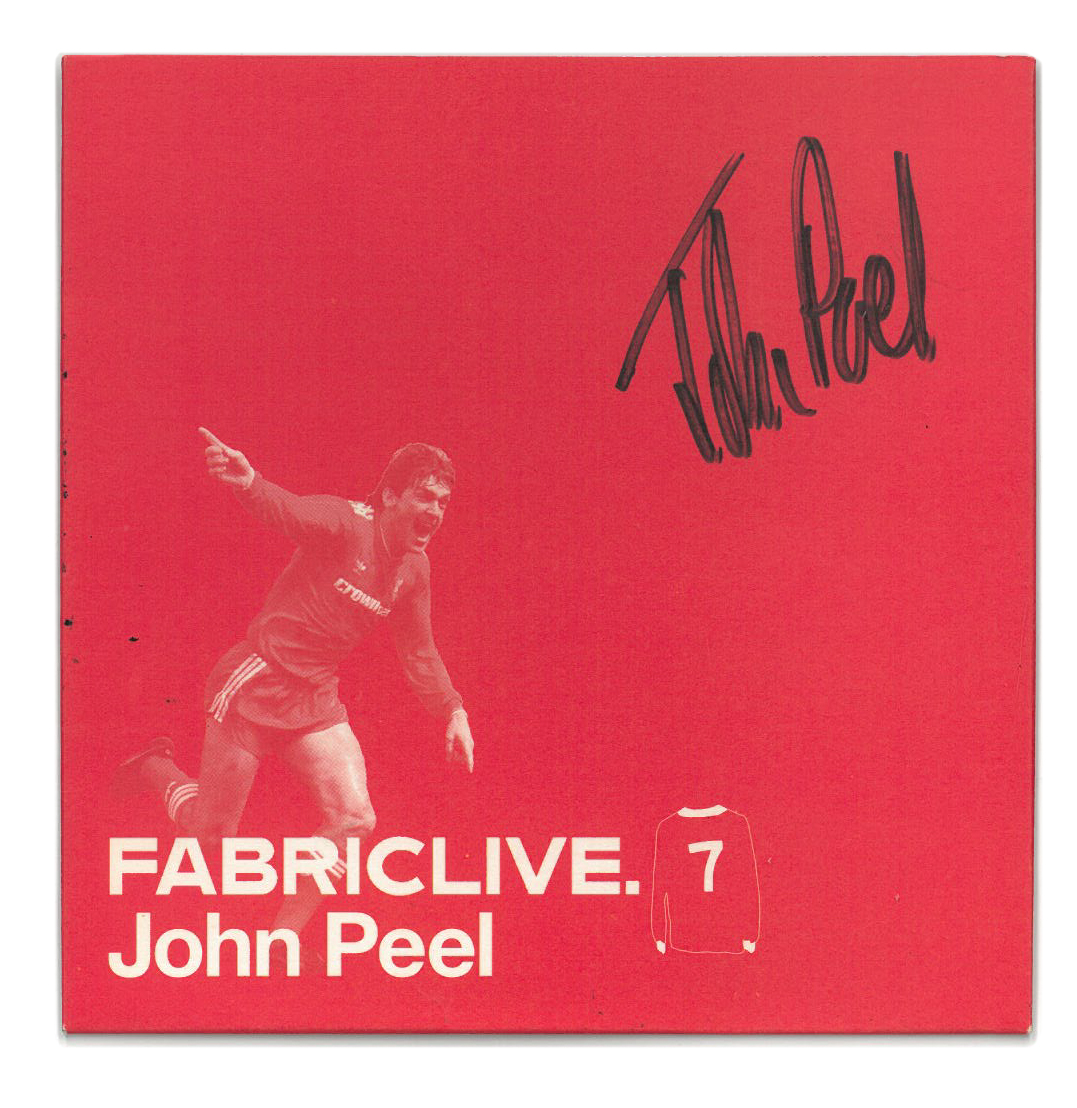

It’s sometime in August 2002, and on London’s Holloway Road four men are huddled into a recording space estate agents would call ‘compact and practical’. At his computer, a studio engineer is encoding vinyl records to lay into a mix. What might normally be a mundane and perfunctory task is enlivened by the man guiding him – Radio 1’s legend-in-his-own airtime, John Peel. The four of us – John, engineer Elliot, Fabric’s record label boss Geoff Muncey and myself – are there to make ‘FABRICLIVE 07’, an early entry in the London club’s CD series that will run for over 15 years.

Having provided a longlist of tracks for us to clear, John gleefully plucks the approved vinyl from his record box – the box which, years later, will have its very own Channel 4 documentary – creating a setlist he’ll come to term “mood-demolishing, rather than mood-building.”

Throughout the day he’s extolled each song’s virtues, being particularly pleased that Joy Division’s ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ – a track never licensed to a compilation and initially refused to Fabric – has been escalated up the chain of command at Warner Music and received a last-minute exception on the basis that it’s for John. Result.

But right now, breaking the mood of creative collaboration, there’s a big problem. John has spent the last five minutes in floods of tears. This itself isn’t a surprise – during the last year of getting to know him and will confirm again many times, tears are common-or-garden Peel behaviour and you never know what mundanity will set him off next. As he told Jockey Slut that same year: “I’m sure a psychoanalyst would come up with something fantastic. Until I met Sheila I don’t remember ever having cried before. Since then, I’ve become absolutely terrible. I’m not proud of it. At times it’s actually very embarrassing.”

Today’s trigger is the recording of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ by the Kop Choir – the sound of Anfield, home of his beloved Liverpool F.C., in full voice (a song that so reliably fires the Peel tear ducts, I even see him lose it one night to a feeble ringtone version on his Nokia).

John wants it to close the mix. It was always his finishing track as a touring DJ - the 70s and 80s incarnation, when he took the John Peel Roadshow to “resentful students who wanted chart hits and beer-drinking competitions” – and he’s convinced that fading out with the Kop singing is the perfect finale.

Huddled in a corner, Geoff agrees with me: the mix should end with the track most synonymous with Peel, ‘Teenage Kicks’ by The Undertones. The air is heavy. John is visibly pissed off with the disagreement, adamant about the issue, and – understandably – feeling a little bullied. It’s a standoff.

It was easy to know if you’d overstepped the mark with John. Sitting in on his radio show for Jockey Slut once, I got bollocked for nattering with his producer, Louise, while a record played: “I’m sorry, am I getting in the way of your conversation?”

Another time, at his 65th Birthday party at Peel Acres – an occasion when, incidentally, I learned of snake-hipped 80s footballer Pat Nevin’s love for both Peel and Jockey Slut – he admonished me for asking if he was having a good time: “Of course I am, it’s my fucking birthday.” (He later told me he found that question condescending from younger people, and I’ve never asked it of anyone older since.)

Even Geoff gets chided today. Casually dipping into Peel’s record box to gawk at THE copy of ‘Teenage Kicks’, the one with John’s handwritten label and asterisk rating, Peel peers over his shoulder and says, firmly: “Would you kindly put that back?”

We break for the day with the tracklist unresolved. As he leaves the building, I ask John if he’s taking his record box home with him. “It’s OK,” he says. “I trust you.”

After he leaves, Geoff and I agree to go with our preferred order. It makes me feel shit just thinking about how we defied John. But that’s nothing compared to how I would have felt had anything happened to that record box. Especially as – being young and stupid – I inexplicably choose to take it with me to my DJ gig at the Elbow Rooms on Old Street later that night.

It’s a completely futile exercise in the end. When I get to the club the little adaptor on the decks is missing so I can’t even play the old 45s I want to because they don’t have a spindle hole. I take it back the next day to finish the mix, the shame and horror of the potential consequences hitting me hard years later.

With the same cloying bravado of a young, idiotic, music industry type, I’d already laid down the start of the mix without John. I’d arrived at the studio a bit before him and used another piece of his favourite vinyl, Peter Jones’ BBC radio commentary of Alan Kennedy’s goal against Real Madrid in the 1981 European Cup Final, over the top of a track I’d heard him play on his show – Asa-Chang & Junray’s hypnotic and beautiful ‘Hana’ (I never did find out what the two experimental musicians from Tokyo made of that).

To start the mix for real, I also loaded in the Soledad Brothers’ 12-bar blues number, ‘Bring it On Down’, which I’d heard played on his radio show a few weeks before and, for the umpteenth time in my life, stopped what I was doing to stare at the radio. In one of those opportunities too good to pass up, the vocal on the Soledad track starts with a spoken line of barroom drawl – ‘My name is Johnny, you deal with me now...’ – giving Peel the ideal platform to work from. I was pretty sure he’d love it, and thankfully I was right. What came next was a set I’d come to know well, with most of the tracks featuring in his prior DJ appearance at Fabric.

That night – Friday, February 1, 2002 – can only be described as Peelmania. I did the warm-up set for him in Fabric’s Room Three – a small club-within-the-club – and you genuinely couldn’t move in there (an eight-months pregnant woman sat on the step next to the DJ booth all night, determined not to miss anything). At one point, observing my attempts at filtering on the mixer, Peel leant in and asked: “Are you actually doing anything there or just trying to look cool?” “A bit of both,” I said, rumbled.

Despite the lack of DJ dexterity, the next two hours were unpretentious muso bliss – track after unexpected track, as gloriously shambolic as his radio shows, capturing the man’s esoteric attitude and lack of prejudice: Status Quo, happy hardcore, dub reggae, rock’n’roll, techno, and country-style cover versions of the Sex Pistols.

At the end of the night – even in those simpler times before omnipresent smartphones and celebrity selfies – it took him a full 15 minutes to leave the club with scores of people shaking his hand, singing ‘Teenage Kicks’, and chanting his name. Out on the street he was scrambled, adrenalin pumping from his performance, unable to remember where his cab should take him.

When asked about his Fabric appearance, he told Jockey Slut: “I was amazed to be asked and very, very scared, and it was just fantastic. It was much better than the gigs I used to do in the 60s, 70s and 80s. They were all nightmarish, not just for me but for the audience. A couple of times I had to be escorted back to my car by a phalanx of policemen and on one occasion, in Silith near Carlisle, I had to be led to the border. So, Fabric was amazing, fantastic. It was as great a night as I’ve had in my life, and people will say: ‘Oh, he would say that wouldn’t he?’, but it actually was. The fact that people were singing ‘Teenage Kicks’ eight minutes after I’d finished was unforgettable.”

John only ever had one non-negotiable demand when playing Fabric, that – having suffered a brain haemorrhage in 1996 and a relapse in 1997 – there would be somewhere safe for his wife Sheila to sit, listen, and have a drink (he remained livid, years later, that a popular comedian had booted Sheila and his family out of one such area at an event he’d compered at Anfield: “just so some of his idiot cronies could sit there.”)

It’s Sheila I speak to on the phone, when I call to get feedback on the promotional copy of ‘FABRICLIVE 07’ with its special cover design featuring Liverpool’s famous number 7, Kenny Dalglish. I should be speaking to John but having seen that we’ve gone against his wishes with the tracklist he’s seemingly refusing to talk to me.

“Don’t worry, he’s just being silly,” says Sheila, “he’s sitting in his favourite chair, drinking red wine, crying. He loves it.”

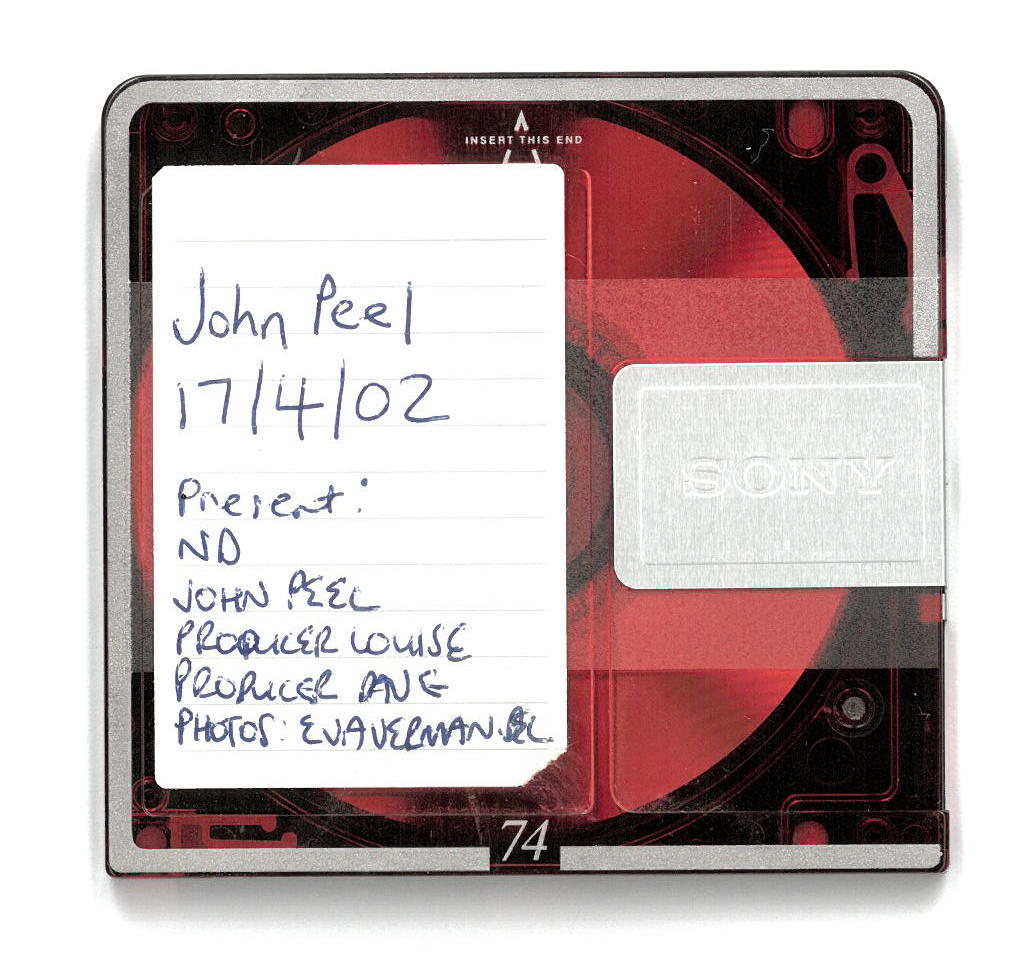

I didn’t have to work hard to get John talking endearingly about Sheila. When I sat down with him for Jockey Slut in April 2002, he spoke at length about her, remembering how he passed her a handwritten note when they first met, how, when they first got together, the song ‘Band of Gold’ seemed to be on the radio every time they had sex, and how he came to nickname her ‘The Pig’. But even that Jockey Slut interview had thrown up its own challenge.

John chose his favourite Thai restaurant in Maida Vale as the venue for our chat – as no-frills and welcoming as you might expect – and, alongside my research, I had a sheet of questions from Jockey Slut readers and musicians associated with him.

During the couple of hours we sat there – captured on my Sony Minidisc which was pretty much equivalent to rocking up with the Metaverse in my pocket – he only refused to go on record with one question: “Is it true you made the beast with two backs with Germaine Greer in the 60s?”

There were two problems with this. First, he hadn’t heard that expression for the physicals before and I had to explain its likely etymology. Second, there’d been some legal drama in the past and, when I investigated it a bit, some to-the-point comments from Germaine about the contents of the Peel Y-fronts, a no doubt justifiable response to his talking out of school. He asked that Jockey Slut not publish anything and, at least for a while, seemed a bit flustered by it all. This being 2002, the awkwardness was broken by everyone at the dinner table lighting up fags, and John going into a tirade about how lovely the smell of tobacco is until it’s lit.

The musicians’ questions floored him, though. When I asked Howie B’s question: “When do you decide what’s going to be played on your radio show?” he shot back, incredulously: “Is that from THE Howie B?” More than any of his other responses, it was this reaction that taught me most about who John was, why he did what he did, and how he’d remained so relevant and dedicated: he never lost his fascination or admiration for musicians. His professional purpose was to wonder at their achievements and promote their endeavours.

This is why his support for happy hardcore and other unpopular genres is so explainable. He liked it enough to play it, sure, but what mattered was that someone had made it in the first place. As he said in the interview: “I like stuff that people think is uncool. I love it when people say to me: ‘You shouldn’t play that, it’s uncool.’ I always think: ‘You’ve completely missed the point’, as they did with punk when I first started playing that. People would write in, really disturbed, saying: ‘You’ve made a terrible mistake. Don’t you understand? This is not good.’ It was exactly the same with happy hardcore – I loved happy hardcore because the dance music fraternity by and large seemed to disapprove of it. Our Thomas adored it. He’d have those box-set things of eight cassettes of somebody’s set at some awful place in Luton. He’d be playing them in his bedroom and I’d think: ‘Actually, that sounds really good.’ So, anything that people tell me I shouldn’t play tends to be what interests me the most.”

On ‘FABRICLIVE 07’ John chose possibly his all-time favourite piece of happy hardcore – ‘Identify the Beat’ by Marc Smith and Safe ‘N Sound. Underlining his point, it completely split the camp at Fabric HQ with a general feeling that it didn’t fit the club’s music policy and should be removed. To his credit, in what was undoubtedly the right decision, Fabric’s owner Keith Reilly kept it in.

For so many years Peel just about survived changing audience tastes and the continual drive to refresh Radio 1 to attract younger demographics (he’d often quote a factoid that the Peel Session had the station’s youngest average audience, which might have been one of those facts no one wanted to check in case it proved to be false).

At that time, he’d also built a parallel audience for his Radio 4 show ‘Home Truths’, focusing on life at Peel Acres, and had become a National Treasure before the term was in full circulation. He never seemed at ease with it, and sometimes it felt like he was hanging on in there, living in fear of the axe or a sideways shunt to a sister station with each successive regime change.

The press campaign for the album backed this up. Convinced we had a shot at the cover of the NME, we were told in no uncertain terms by the Editor that: “Peel is too Radio 4 these days, he’s not really for us.”

What was true was that his Radio 1 counterparts – Pete Tong, Gilles Peterson, Fabio & Grooverider – were popular, contemporary, club and festival DJs and, save the odd appearance at the Sonar Festival or Tribal Gathering, Peel was very much not. Which might be why he met playing at Fabric with such enthusiasm.

In what was to be one of the final times I saw John, we were sat in a Smithfield pub, The Butcher’s Hook and Cleaver, having a drink after some Fabric promotional work. I asked him how his autobiography was coming along and what deadline he’d been given. “They haven’t given me one,” he said, “so I suppose it’s just the ultimate deadline.”

As the pub’s name suggests, ‘The Butchers’ sits directly opposite the Smithfield Meat Market and, right next to it, is a small but pristinely maintained garden - the Smithfield Rotunda. The gate to the Rotunda is opened every day and, years later, I realised that’s probably for the benefit of patients at nearby St Bart’s hospital. For the Fabric team, it’s usually the pub’s unofficial beer garden and we would head there most sunny evenings.

On this cold morning – Tuesday, October 26, 2004 – I’m in the Rotunda alone, reeling from the news John has died whilst on holiday in Peru. I send a text to his son, Tom, but beyond that I’ve no idea what to do. In the coming days I’ll write to Sheila, as thousands of others do, and give quotes to the music press on behalf of the club. Fabric immediately donates the revenue raised from ‘FABRICLIVE 07’ to Médecins Sans Frontières, John’s favoured charity.

Two weeks later, I’ve borrowed my dad’s battered Peugeot 406 Estate to take the road to Bury St Edmonds for his funeral. Despite offers I’ve elected to go on my own, which turns out to be a mistake. Flying solo at a wedding makes you feel like a novelty; doing it at a funeral makes you feel like an oddity.

This becomes clearest when, as available car seats are divvied up to get people from the service back to Peel Acres, the brilliant American singer-songwriter, Nina Nastasia, wins the Shitbox Lottery and gets a spot in the 406. The car is filthy on the outside and much worse inside, and the experience seems to top off a quite wonderful day for poor Nina.

To break the ice, I ask her if she wants some music on. Getting the merest shrug, I pass her my ‘radio on a rope’ which I’ve brought along from my shower at home because dad’s car stereo is knackered. She doesn’t laugh and we putter off, very slowly, in silence.

The service had a fitting sense of occasion, with hundreds congregating on the Cathedral of St. James’ lawn, listening to a broadcast on a PA. Inside I’m reduced to audio-only too. In my haste to sit down I’ve taken a seat directly behind a huge pillar. John’s producer Louise comes to re-seat me with her nearer the front, but for whatever reason I decline. I’m sat next to Jo Whiley, but it isn’t the time to tell her how great I think she is so – fittingly – I spend the time in silence, just listening.

The service is exquisite. We hear Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Going Down Slow’ which might be the most apt funeral song possible, and a reading of Shelley’s poem, ‘Love’s Philosophy’ – a final paean to Sheila, ending with the gut punch: “What is all this sweet work worth/If thou kiss not me?” Then on the lighter side there’s some top-grade reminiscence from John’s brother Alan who, remarking on how to be more successful with women, provides a canonical piece of advice to John: “Just always remember, they like it too.”

The service is top-and-tailed by John himself. Firstly, his entrance to the cathedral, carried by his family. As our heads turn in the pitched silence it’s like a single, shuffling, snuffling mass, the awe of the moment plain to all. And at the end, cutting through the dense atmosphere is his voice – played to us one last time: “I’m fabulously lucky, I’ve got everything I wanted as a kid, a house in the country, an astounding wife, and a job on the radio. I don’t know what could be done to improve it. If I drop dead tomorrow, I’ll have nothing to complain about – except that there’ll be another Fall album out next year and I won’t get to hear it.” It’s warm, unexpected, and somehow reassuring.

Then right at the end, someone presses play on ‘FABRICLIVE 07’ and the Kop Choir sings ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, the track never seeming so apposite. As the strains fade, just as I’d heard a hundred times prior, there’s Billy Doherty’s short drum intro, a clang of John O’Neill’s guitar, and the urgent scream of Feargal Sharkey’s vocal as ‘Teenage Kicks’ erupts into the vast space.

I’m sorry John, but I think that settles it. It really was the only way it could end.

“I remember when he played...”

“I was heading to Final Frontier in my second-hand Volvo 440 when I heard John play my remix of the Chemical Brothers. I was astonished. I mean, John had already been extremely supportive with previous tracks I had made or remixed, but here was John again beating all the other specialist DJs on Radio One by some weeks. I went into that club on cloud nine. Whenever John played my music or remixes I always seemed to be in a car thinking ‘wow’ and each time felt as special as the first.”

Dave Clarke

“I remember hearing him play ‘Hong Kong Garden’ - it was probably 1978. I just said: that’s fucking it! Ten years later, I was mixing Siouxsie and the Banshees in London. Mental!”

Howie B

“I remember when he played our cover of Prince’s ‘Sign of the Times’, ‘Sine of the Dub’ back in 2004. It was the first release on Hyperdub and I’d been told he was going to play it. At that moment, I was driving around the motorways of Glasgow and I tuned in excitedly to hear the first time some of my music had been played on national radio. Much to my surprise, instead of playing the track at 33rpm, for some reason he played it at 45rpm. Instead of a slow motion, deep and dubbed out slice of dub poetry, it turned into something much funnier.”

Kode9

“I remember when he played a track by Pere Ubu, ‘The Final Solution’. I think it would have been late 1976, as I was at college in High Wycombe. It was such a weird track to play at a time when we were still in the fag end of pub rock - such a blast of energy, it just blew me away. The next day I went up to London to hunt out a copy – Rough Trade possibly. I bought the 7-inch and I still have it.”

Jonathan More, Coldcut

“The first time I heard Underground Resistance, early releases on Warp Records, and grime was on his show. All of which went on to have a big influence on my musical life. I’ll always be grateful for that. I loved the fact that whoever tuned into John Peel‘s radio show was always going to hear something unexpected or unknown that may turn out to be really significant to the musical landscape.”

Surgeon

This article first appeared in issue one of Disco Pogo.

.svg)