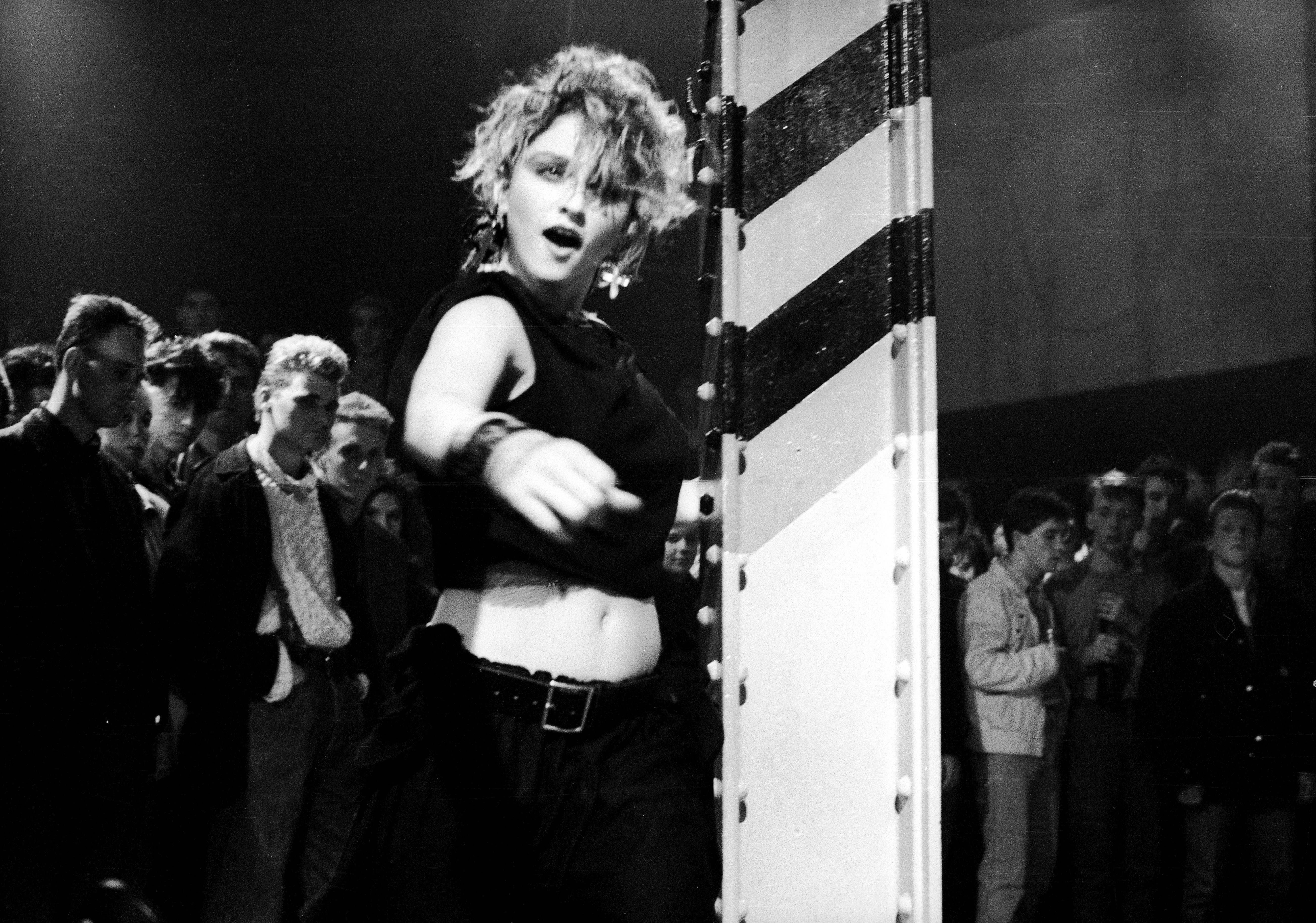

When Madonna appeared at The Haçienda in 1984, she was a relative unknown. Within 12 months she was the coolest pop star on the planet. Could pioneering DJ Greg Wilson have predicted such a meteoric rise when he witnessed her performance at FAC 51? As he recounts, possibly not. Manchester, as ever, so much to answer for…

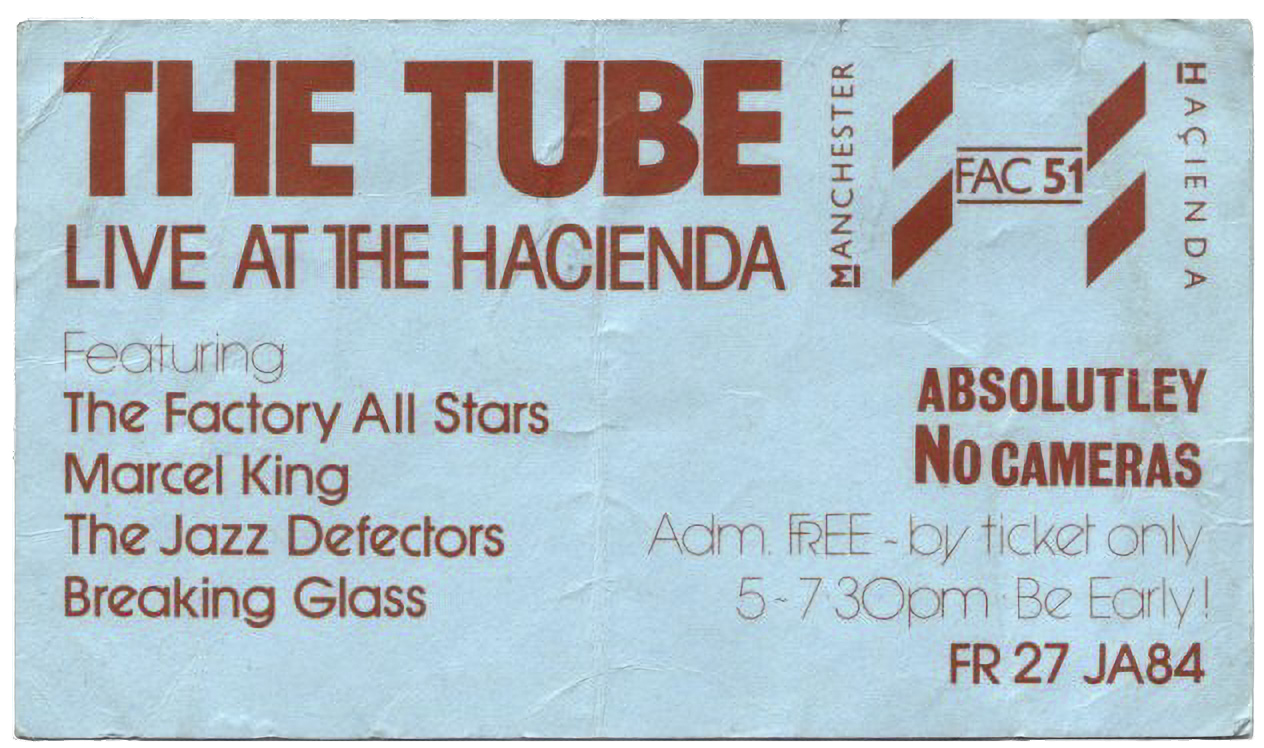

On Friday 27 January 1984, Madonna performed one of her earliest shows in Europe (she’d done the promo circuit the year before taking in London’s Le Beat Route, a couple of appearances at Camden Palace and some Italian TV spots). However, rather than some night-time soiree – the kind she was used to back home in New York – this was a late-afternoon slot as part of a special outside broadcast of the Channel 4 TV music programme, ‘The Tube’, which was normally filmed live from Tyne Tees TV studios in Newcastle. The venue, on the other hand, she would have been comfortable in. That week’s edition of ‘The Tube’ was filmed at the Factory Records-owned nightclub, The Haçienda, itself inspired by New York’s clubs like Danceteria, Funhouse, The Roxy and Paradise Garage, among others.

The broadcast was a big occasion for The Haçienda, which had struggled to establish itself following its May 1982 opening, an opportunity for the venue to announce itself to a wider audience – the event even given its own Factory Records catalogue number, FAC 104. This was four years before 1988’s second summer of love, which launched the club into national and, consequently, international fame.

Madonna was a late addition to the line-up, her name not mentioned on the tickets. The Factory All-Stars, consisting of members of New Order, Quando Quango, The Wake, A Certain Ratio and 52nd Street, was the most anticipated performance, whilst the former Sweet Sensation singer, Marcel King, showcased his own Factory release, ‘Reach for Love’. Local dance heroes The Jazz Defectors and Broken Glass (mis-billed as Breaking Glass) completed the advertised line-up.

Although it was ‘The Tube’ who’d directly booked Madonna, rather than a Haçienda suggestion, it was highly coincidental given she had previous history with Factory, dating back to New York in December 1982, when the singer supported A Certain Ratio at the influential downtown arts venue, Danceteria, her very first solo gig. She performed just one song, her debut single, ‘Everybody’, which had been released in the US a few months earlier.

I first came across Madonna via an import 12-inch of ‘Everybody’. I had no idea who she was or what she looked like. The sleeve for the 12-inch was a vividly colourful street collage, clearly set against a Black urban landscape – there was no image of the artist. At the outset it was all about aligning her to a club audience with the illusion of Blackness to enhance the record’s street credibility.

Listening to ‘Everybody’, it was clearly a white vocalist, but it wasn’t the song I was interested in personally, but the largely instrumental dub mix on the flip – back then, dubs and instrumental versions were generally preferred to the main vocal sides in the underground clubs, revered for their more experimental nature. That year was a groundbreaking year for dance music, opening up a vista of new electronic possibilities that DJs, remixers and producers, spearheaded by the likes of Arthur Baker, François Kevorkian, Larry Levan, Shep Pettibone and John ‘Jellybean’ Benitez, wasted no time in exploring.

Madonna had recorded a demo of ‘Everybody’, and Mark Kamins, the DJ at Danceteria, offered his help in finding a label to release it, whilst becoming the singer’s boyfriend of the time. Kamins produced and mixed ‘Everybody’ as her debut single, the record blowing-up in the New York clubs. Factory’s relationship with Kamins was further cemented when his mix of Quando Quango’s ‘Love Tempo’ took the group into the US dance chart in 1983 (Kamins would also remix Marcel King’s ‘Reach for Love’ and, later in 1984, become the first US DJ to play at The Haçienda).

Whilst ‘Everybody’, plus the 1983 follow-up, ‘Burning Up’/‘Physical Attraction’ (this time produced by Reggie Lucas), both reached number three on the US dance chart, they pretty much passed without notice in the UK. Madonna’s self-titled debut album, released in the US in the summer of 1983, would only enter the charts, on both sides of the Atlantic, the following February.

This was facilitated by the success of her third single, ‘Holiday’, written by Curtis Hudson and Lisa Stevens-Crowder of the NYC dance act, Pure Energy. It was a top 20 hit in the US that did better still in the UK, where it provided Madonna with her first top 10 hit anywhere. Produced by Jellybean Benitez, who would become her new beau, it was initially a slow-burner, entering the UK chart at number 53, before climbing to number 40 on 21 January, the week of ‘The Tube’. Her appearance was undoubtedly a factor in the single’s subsequent success, which would peak at number six the following month (re-entering the chart in 1985, this time reaching number two).

At The Haçienda, then, there was no great fanfare for the future Queen of Pop, instead the Manchester audience stood statuesque, some with folded arms, as Madonna, up close on the dancefloor, and her two dancers (her brother, Christopher Ciccone and Erika Belle) worked their bodies as she lip-synced to ‘Burning Up’ and ‘Holiday’. This was at the time when the all-action street style of breakdancing was exploding in the UK. The city’s main exponents, Broken Glass, who I then managed, accompanied Marcel King’s performance, so Madonna’s choreographed routine seemed a little tame in this context. It was also way too poppy for the Haçienda regulars, then largely students and indie kids, often with a distaste for dance music and especially contemptuous towards performers miming. Some people claimed to have glimpsed her star potential, including the Guardian writer, Tim de Lisle, who recalled, some years later, that “she mesmerised the crowd – you just knew there was a personality there”.

From my own observation, there was nothing to suggest we were watching one of the superstars of the late-20th century, the audience displaying collective indifference, rather than being under some mesmeric spell. I remember, a few years later, seeing a teenage Whitney Houston perform at a DJ event in London before she’d released a record and it was clear to all that she was someone destined for big things; not something you could have confidently said about Madonna that day.

What was more insightful was her backstage persona. It was clear she knew that she was going places, regardless of what anyone else thought. Whilst exchanging some banter with the Broken Glass guys, I also remember her being somewhat moody and demanding, already playing the diva role and giving some of the Haçienda staff/TV crew the runaround. She was a bundle of attitude, who demanded star treatment. When her tour manager introduced her to Mike Pickering, he pointed out that Pickering was friends with Mark Kamins (not the best of icebreakers, given Madonna had moved on from her professional and personal relationships with Kamins) and that he was responsible for ‘Love Tempo’ by Quando Quango, the big New York club hit. “Oh, that dross,” was dismissively offered in spite-filled response.

What would later occur to me was that it wasn’t just Madonna, but a handful of artists congregated backstage that day, who’d go on to have number one hits. Norman Cook, who we’d met the previous month in Brighton, when I DJed for The Haçienda Review, a short tour of the south, which featured Quando Quango and Broken Glass, had come to Manchester for ‘The Tube’. He stayed with Kermit, then one of the Broken Glass crew, but soon to move from breakdancing to rap. Norman would hit the peak with The Housemartins, Beats International and as Fatboy Slim; Kermit would land a number one album with Black Grape, in partnership with Shaun Ryder, previously of Factory’s Happy Mondays.

.jpg)

Mike Pickering, prior to his legendary DJ role at the club, was then the booker for The Haçienda, but also a musician with Quando Quango and later T-Coy, before hitting the top spot with M People. There were various members of New Order floating around and although I never saw him backstage, Morrissey was interviewed on the balcony, The Smiths having recently made their chart breakthrough.

Including Madonna, that’s six future chart toppers, but we shouldn’t forget that only one of the people there that day, Marcel King, held the distinction of having scored a number one hit prior to that evening, Sweet Sensation’s ‘Sad Sweet Dreamer’ going all the way ten years earlier, in 1974, when he was a teenager. ‘Reach for Love’ would be his swansong, finding favour in the US clubs, but overlooked here. As he returned to the obscurity of his post-Sweet Sensation years, Madonna’s meteoric rise was gaining full momentum, her first US chart topper, ‘Like a Virgin’ coming the following Christmas (a UK number one was delayed until the arrival of ‘Into the Groove’, in the summer of 1985).

Rob Gretton, New Order’s manager and The Haçienda co-owner, was said to have offered Madonna £50 to stick around in the club to repeat her performance that night. She was neither interested nor impressed, inviting Gretton to “fuck off” before making a hasty exit. Some years on, when she met Tony Wilson, he received an ‘ice-cold stare’ on reminding her that she’d played his club. “My memory seems to have wiped that,” she snarkily replied.

Her dancing brother, Christopher, hadn’t wiped the memories, however. In his 2008 book, ‘Life With My Sister Madonna’, he recalled ‘The Tube’ appearance. “Usually during ‘Holiday’ the crowd gets in the mood and starts dancing, but not this time,” he recalled. “They just stand still and watch, faces impassive. Then, suddenly, they start booing and throwing things at us. I’m hit with a crumpled up napkin, Madonna with a roll, Erika with something else. We’re stunned. It’s obvious that this isn’t about music, it’s about us. With cash in hand, we bolt.”

And so, it ended, a brief, but fascinating moment in pop culture, when a future global star came to a soon-to-be iconic club to announce her presence on a cult UK TV show. Who’d have thought, as she mouthed the words to ‘Holiday’ on The Haçienda dancefloor that day, that the following month this would become her first of over 60 Top 10 UK hits, a remarkable figure only surpassed in the history books by Elvis Presley and Cliff Richard. None of us saw that.

Read: Madonna's greatest inspiration. Her enduring relationship with the dancefloor

Read: How Madonna's first album changed everything

Read: Madonna's 12 best dancefloor 12-inches

This article first appeared in issue seven of Disco Pogo.

.svg)

.jpg)